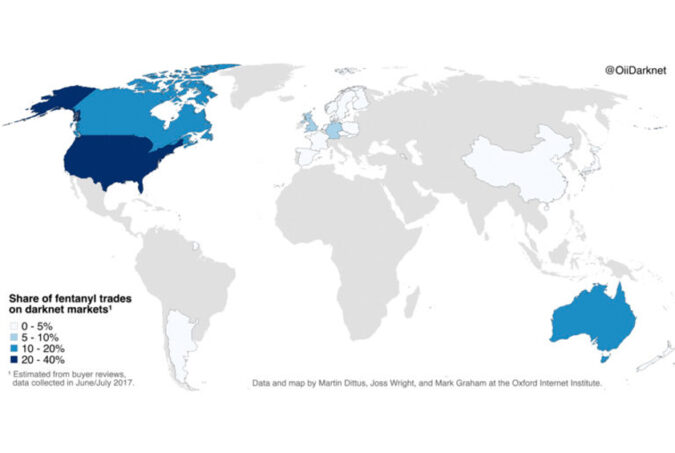

My colleagues Joss Wright, Martin Dittus and I have been scraping the world’s largest darknet marketplaces over the last few months, as part of our darknet mapping project. The data we collected allow us to explore a wide range of trading activities, including the trade in the synthetic opioid Fentanyl, one of the drugs blamed for the rapid rise in overdose deaths and widespread opioid addiction in the US. The map shows the global distribution of the Fentanyl trade on the darknet. The US accounts for almost 40% of global darknet trade, with Canada and Australia at 15% and 12%, respectively. The UK and Germany are the largest sellers in Europe with 9% and 5% of sales. While China is often mentioned as an important source of the drug, it accounts for only 4% of darknet sales. However, this does not necessarily mean that China is not the ultimate site of production. Many of the sellers in places like the US, Canada, and Western Europe are likely intermediaries rather than producers themselves. In the next few months, we’ll be sharing more visualisations of the economic geographies of products on the darknet. In the meantime you can find out more about our work by Exploring the Darknet in Five Easy Questions. Follow the project here: https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/research/projects/economic-geog-darknet/ Twitter: @OiiDarknet

The US accounts for almost 40% of global darknet trade, with Canada and Australia at 15% and 12%, respectively.