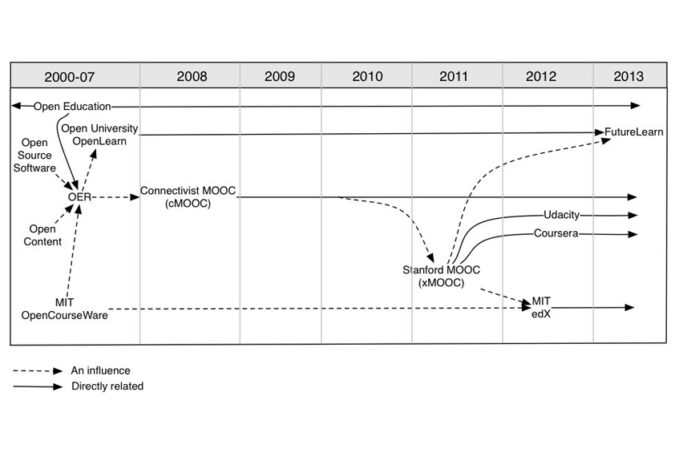

Timeline of the development of MOOCs and open education, from: Yuan, Li, and Stephen Powell. MOOCs and Open Education: Implications for Higher Education White Paper. University of Bolton: CETIS, 2013.

Ed: Does research on MOOCs differ in any way from existing research on online learning? Rebecca: Despite the hype around MOOCs to date, there are many similarities between MOOC research and the breadth of previous investigations into (online) learning. Many of the trends we’ve observed (the prevalence of forum lurking; community formation; etc.) have been studied previously and are supported by earlier findings. That said, the combination of scale, global-reach, duration, and “semi-synchronicity” of MOOCs have made them different enough to inspire this work. In particular, the optional nature of participation among a global-body of lifelong learners for a short burst of time (e.g. a few weeks) is a relatively new learning environment that, despite theoretical ties to existing educational research, poses a new set of challenges and opportunities. Ed: The MOOC forum networks you modelled seemed to be less efficient at spreading information than randomly generated networks. Do you think this inefficiency is due to structural constraints of the system (or just because inefficiency is not selected against); or is there something deeper happening here, maybe saying something about the nature of learning, and networked interaction? Rebecca: First off, it’s important to not confuse the structural “inefficiency” of communication with some inherent learning “inefficiency”. The inefficiency in the sub-forums is a matter of information diffusion—i.e., because there are communities that form in the discussion spaces, these communities tend to “trap” knowledge and information instead of promoting the spread of these ideas to a vast array of learners. This information diffusion inefficiency is not necessarily a bad thing, however. It’s a natural human tendency to form communities, and there is much education research that says learning in small groups can be much more beneficial / effective than large-scale learning. The important point that our work hopes to make is that the existence and nature of these communities seems to be influenced by the types of topics that are being discussed…