All Articles

All topics

-

How to Decolonise the State of Policy in the Digital Space

In his latest editorial for Policy and Internet, John Hartley argues that a whole-of-humanity effort…

-

OpenAI may have rehired Sam Altman, but AI needs more accountability, not ‘geniuses’

– in ToolsThe OpenAI employees had faith in Altman. They believed in his vision and they did…

-

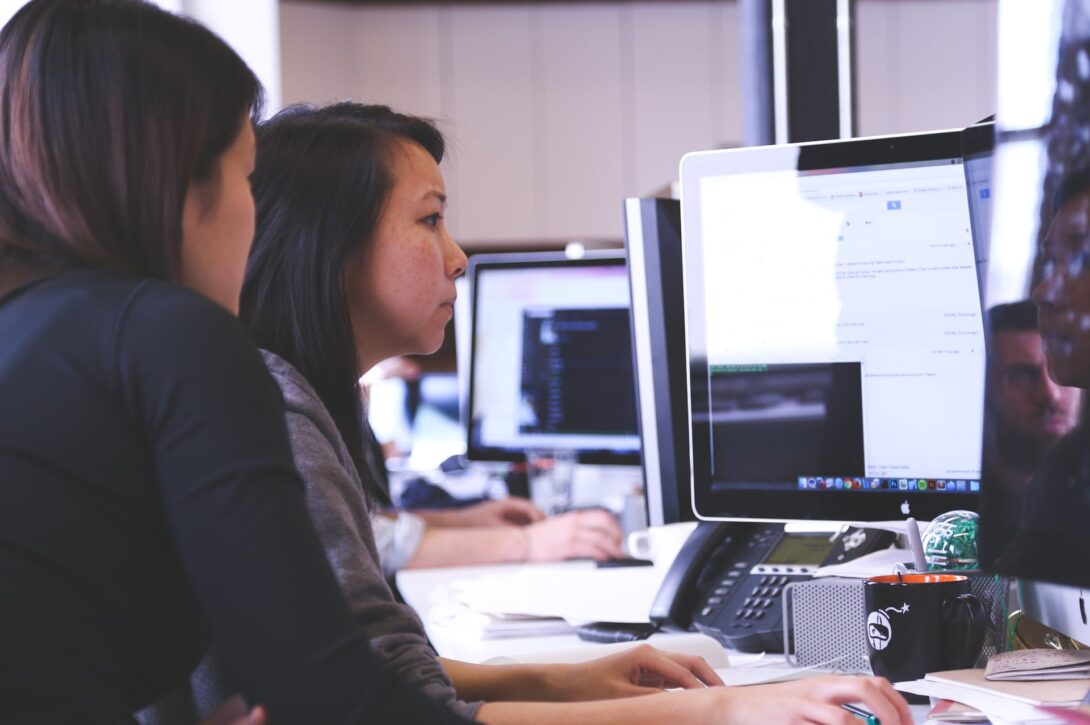

Diversity, Inclusivity, and Good Governance: Emerging themes from the Policy & Internet Conference, 2023

– in ConferencesThe conference brought together leading local and international scholars and practitioners from the fields of…

-

Policy & Internet Conference 2023: Policy innovation for inclusive internet governance

– in ConferencesTogether, scholars and policymakers will discuss current practices, alternative designs and the ‘unknowns’ that are…

-

Policy & Internet Conference 2022: Datafication. Platformisation. Metaverse. The state of global internet policy

– in ConferencesExamining how the current developments within digital media spaces has a regulatory impact.

-

Special Issue Call for Papers – The Regulation Turn?

Do these technologies offer ease of connectivity, or do they have the potential to be…

-

Five reasons ‘technological solutions’ are a distraction from the Irish border problem

Discussing the focus on ‘technological solutions’ in the context of the Irish border debate.

-

Can “We the People” really help draft a national constitution? (sort of..)

There is a clear trend of greater public participation in the process of constitution making,…