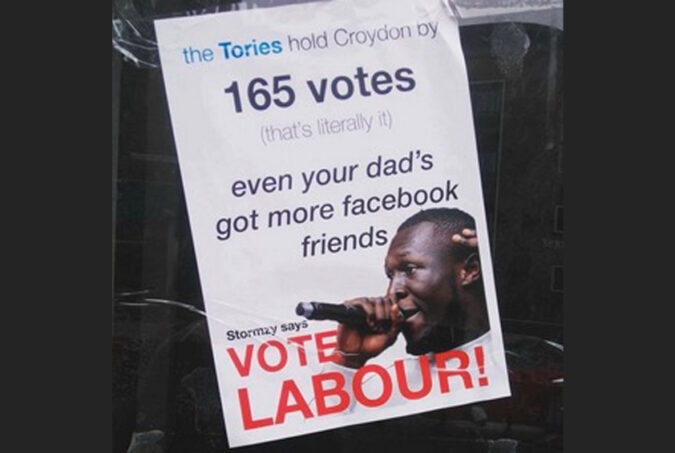

After its initial appearance as a cynical but safe device by Teresa May to ratchet up the Conservative majority, the UK general election of 2017 turned out to be one of the most exciting and unexpected of all time. One of the many things for which it will be remembered is as the first election where it was the social media campaigns that really made the difference to the relative fortunes of the parties, rather than traditional media. And it could be the first election where the right wing tabloids finally ceded their influence to new media, their power over politics broken according to some. Social media have been part of the UK electoral landscape for a while. In 2015, many of us attributed the Conservative success in part to their massive expenditure on targeted Facebook advertising, 10 times more than Labour, whose ‘bottom-up’ Twitter campaign seemed mainly to have preached to the converted. Social media advertising was used more successfully by Leave.EU than Remain in the referendum (although some of us cautioned against blaming social media for Brexit). But in both these campaigns, the relentless attack of the tabloid press was able to strike at the heart of the Labour and Remain campaigns and was widely credited for having influenced the result, as in so many elections from the 1930s onwards. However, in 2017 Labour’s campaign was widely regarded as having made a huge positive difference to the party’s share of the vote—unexpectedly rising by 10 percentage points on 2015—in the face of a typically sustained and viscious attack by the Daily Mail, the Sun and the Daily Express. Why? There are (at least) three reasons. First, increased turnout of young people is widely regarded to have driven Labour’s improved share of the vote—and young people do not in general read newspapers not even online. Instead, they spend increasing proportions of their time on social media platforms on mobile…

It could be the first election where the right wing tabloids finally ceded their influence to new media.