Category: Interviews

All topics

-

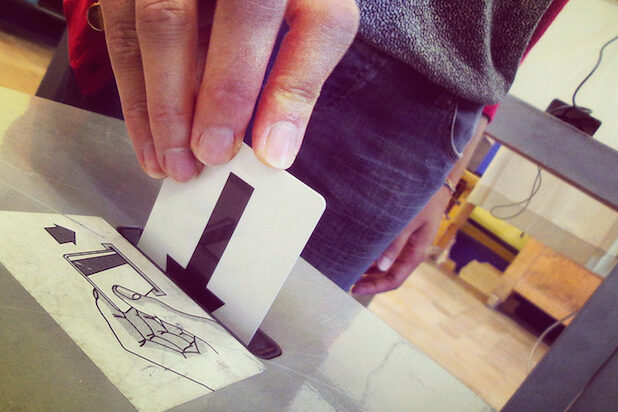

Does Internet voting offer a solution to declining electoral turnout?

While a technological fix probably won’t address the underlying reasons for low turnout, it could…

-

Introducing Martin Dittus, Data Scientist and Darknet Researcher

Martin Dittus is a Data Scientist at the Oxford Internet Institute. The stringent ethics process…

-

Digital platforms are governing systems—so it’s time we examined them in more detail

It’s important that we take a multi-perspective view of the role of digital platforms in…

-

Open government policies are spreading across Europe—but what are the expected benefits?

Mapping out the different meanings of open government, and how it is framed by different…

-

Does Twitter now set the news agenda?

Matthew A. Shapiro and Libby Hemphill examine the extent to which he traditional media is…

-

We should pay more attention to the role of gender in Islamist radicalisation

– in InterviewsUnderstanding how men and women become violent radicals, and the differences there might be between…

-

What are the barriers to big data analytics in local government?

Examining the extent to which local governments in the UK are using intelligence from big…

-

What explains variation in online political engagement?

Examining the supply of channels for digital politics distributed by Swedish municipalities and understanding the…