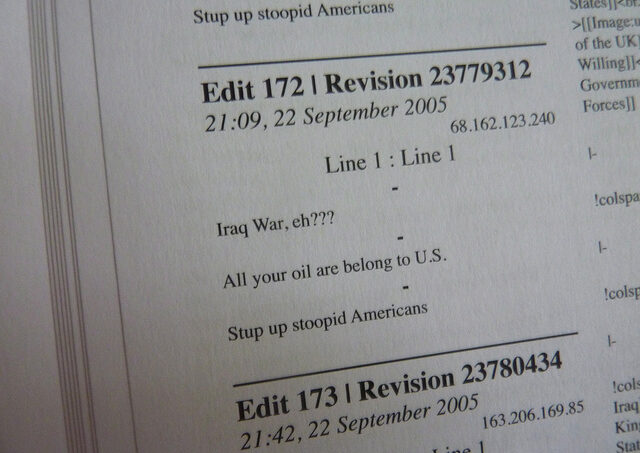

Ed: You examined the voluntary provision by commercial sites of information privacy protection and control under the self-regulatory policy of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC). In brief, what did you find? Yong Jin: First, because we rely on the Internet to perform almost all types of transactions, how personal privacy is protected is perhaps one of the important issues we face in this digital age. There are many important findings: the most significant one is that the more popular sites did not necessarily provide better privacy control features for users than sites that were randomly selected. This is surprising because one might expect “the more popular, the better privacy protection”—a sort of marketplace magic that automatically solves the issue of personal privacy online. This was not the case at all, because the popular sites with more resources did not provide better privacy protection. Of course, the Internet in general is a malleable medium. This means that commercial sites can design, modify, or easily manipulate user interfaces to maximise the ease with which users can protect their personal privacy. The fact that this is not really happening for commercial websites in the U.S. is not only alarming, but also suggests that commercial forces may not have a strong incentive to provide privacy protection. Ed: Your sample included websites oriented toward young users and sensitive data relating to health and finance: what did you find for them? Yong Jin: Because the sample size for these websites was limited, caution is needed in interpreting the results. But what is clear is that just because the websites deal with health or financial data, they did not seem to be better at providing more privacy protection. To me, this should raise enormous concerns from those who use the Internet for health information seeking or financial data. The finding should also inform and urge policymakers to ask whether the current non-intervention policy (regarding commercial websites…

Examining the voluntary provision by commercial sites of information privacy protection and control under the self-regulatory policy of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC).