Author: David Sutcliffe

All topics

-

Psychology is in Crisis: And Here’s How to Fix It

It seems that in psychology and communication, as in other fields of social science, much…

-

Five Pieces You Should Probably Read On: Reality, Augmented Reality and Ambient Fun

Things you should probably know, and things that deserve to be brought out for another…

-

Exploring the world of digital detoxing

Advocates of “digital detoxing” view digital communication as eroding our ability to concentrate, to empathise,…

-

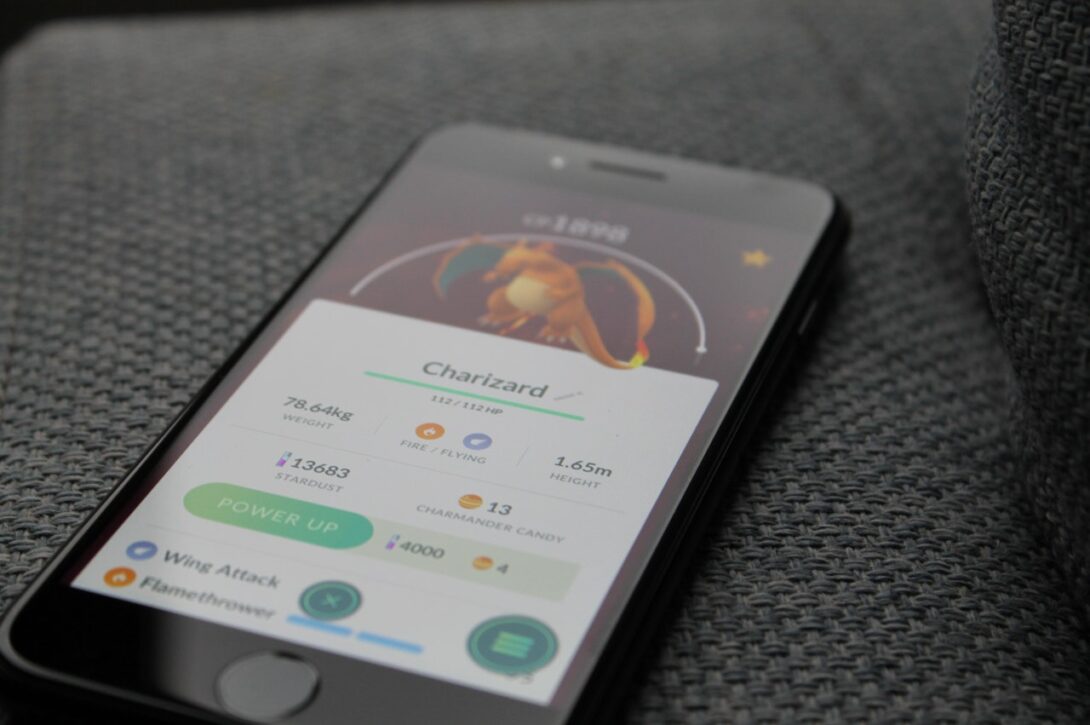

Is internet gaming as addictive as gambling? (no, suggests a new study)

New research suggests that very few of those who play internet-based video games have symptoms…

-

The economic expectations and potentials of broadband Internet in East Africa

Were firms adopting internet, as it became cheaper? Had this new connectivity had the effects…

-

The “IPP2012: Big Data, Big Challenges” conference explores the new research frontiers opened up by big data as well as its limitations

– in ConferencesBig data generation and analysis requires expertise and skills which can be a particular challenge…