All Articles

All topics

-

How ready is Africa to join the knowledge economy?

– in DevelopmentIncreasing connectivity has sparked many hopes for the democratisation of knowledge production in sub-Saharan Africa.

-

What explains variation in online political engagement?

Examining the supply of channels for digital politics distributed by Swedish municipalities and understanding the…

-

Social media is nothing like drugs, despite all the horror stories

– in WellbeingIn reality, social media can have both positive and negative outcomes.

-

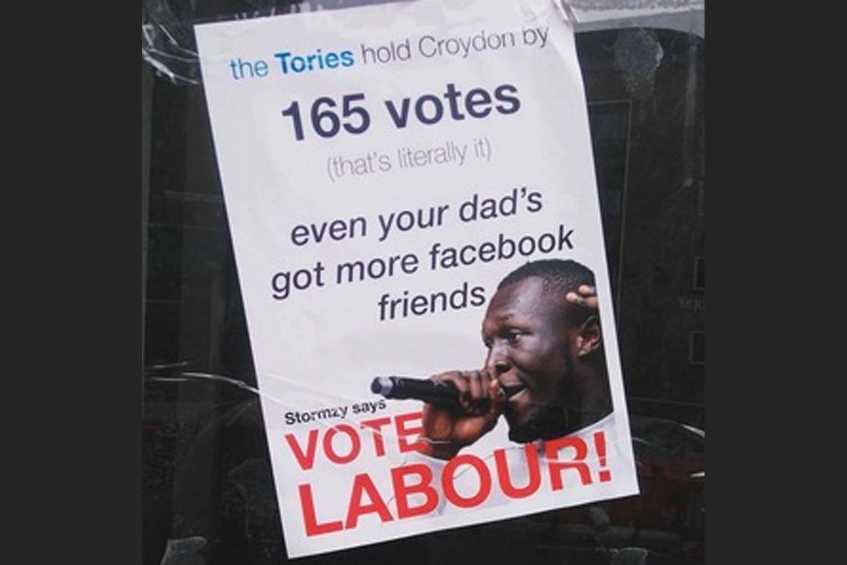

Stormzy 1: The Sun 0—Three Reasons Why #GE2017 Was the Real Social Media Election

It could be the first election where the right wing tabloids finally ceded their influence…

-

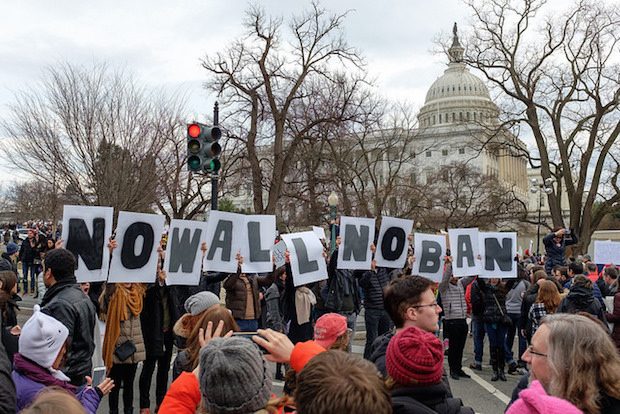

Latest Report by UN Special Rapporteur for the Right to Freedom of Expression is a Landmark Document

– in EthicsWhat is the responsibility of the private industry, which runs and owns much of the…

-

Could Voting Advice Applications force politicians to keep their manifesto promises?

A number of studies have shown that VAA use has an impact on the cognitive…

-

Using Open Government Data to predict sense of local community

Advocates hope that opening government data will increase government transparency, catalyse economic growth, address social…

-

Should adverts for social casino games be covered by gambling regulations?

Notably, nearly 90 percent of the advertisements contained no responsible or problem gambling language, despite…

-

How useful are volunteer crisis-mappers in a humanitarian crisis?

Concerns have been raised about the quality of amateur mapping and data efforts, and the…

-

Is Left-Right still meaningful in politics? Or are we all just winners or losers of globalisation now?

The Left–Right dimension is the most common way of conceptualising ideological difference. But in an…