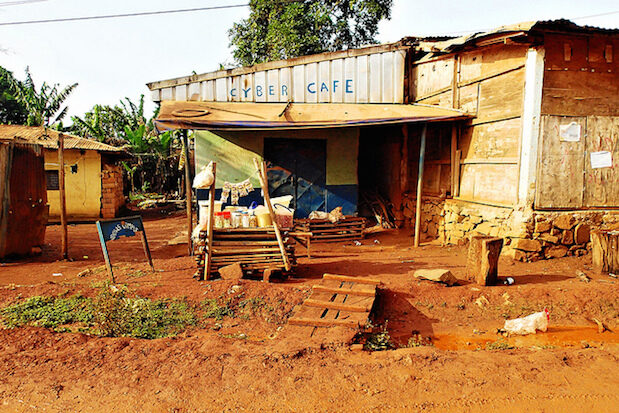

The last decade has seen a rapid growth of Internet access across Africa, although it has not been evenly distributed. Cameroonian Cybercafe by SarahTz (Flickr CC BY 2.0).

There is a consensus among researchers that ICT is an engine for growth, and it’s also considered by the OECD to be a part of fundamental infrastructure, like electricity and roads. The last decade has seen a rapid growth of Internet access across Africa, although it has not been evenly distributed. Some African countries have an Internet penetration of over 50 percent (such as the Seychelles and South Africa) whereas some resemble digital deserts, not even reaching two percent. Even more surprisingly, countries that are seemingly comparable in terms of economic development often show considerable differences in terms of Internet access (e.g., Kenya and Ghana).

Being excluded from the Internet economy has negative economic and social implications; it is therefore important for policymakers to ask how policy can bridge this inequality. But does policy actually have an effect on these differences? And if so, which specific policy variables? In their Policy & Internet article “Crossing the Digital Desert in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does Policy Matter?”, Robert Wentrup, Xiangxuan Xu, H. Richard Nakamura, and Patrik Ström address the dearth of research assessing the interplay between policy and Internet penetration by identifying Internet penetration-related policy variables and institutional constructs in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is a first attempt to investigate whether Internet policy variables have any effect on Internet penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa, and to shed light on them.

Based on a literature review and the available data, they examine four variables: (i) free flow of information (e.g. level of censorship); (ii) market concentration (i.e. whether or not internet provision is monopolistic); (iii) the activity level of the Universal Service Fund (a public policy promoted by some governments and international telecom organizations to address digital inclusion); and (iv) total tax on computer equipment, including import tariffs on personal computers. The results show that only the activity level of the USF and low total tax on computer equipment are significantly positively related to Internet penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa. Free flow of information and market concentration show no impact on Internet penetration. The latter could be attributed to underdeveloped competition in most Sub-Saharan countries.

The authors argue that unless states pursue an inclusive policy intended to enhance Internet access for all its citizens, there is a risk that the skewed pattern between the “haves” and the “have nots” will persist, or worse, be reinforced. They recommend that policymakers promote the policy instrument of Universal Service and USF and consider substituting tax on computer equipment with other tax revenues (i.e. introduce consumption-friendly incentives), and not to blindly trust the market’s invisible hand to fix inequality in Internet diffusion.

We caught up with Robert to discuss the findings:

Ed.: I would assume that Internet penetration is rising (or possibly even booming) across the continent, and that therefore things will eventually sort themselves out—is that generally true? Or is it already stalling/plateauing, leaving a lot of people with no apparent hope of ever getting online?

Robert: Yes, generally we see a growth in Internet penetration across Africa. But it is very heterogeneous and unequal in its character, and thus country-specific. Some rich African countries are doing quite well whereas others are lagging behind. We have also seen known that Internet connectivity is vulnerable due to the political situation. The recent shutdown of the Internet in Cameroon demonstrates this vulnerability.

Ed.: You mention that “determining the causality between Internet penetration and [various] factors is problematic”—i.e. that the relation between Internet use and economic growth is complex. This presumably makes it difficult for effective and sweeping policy “solutions” to have a clear effect. How has this affected Internet-policy in the region, if at all?.

Robert: On the one hand one can say that if there is economic growth, there will be money to invest in Internet infrastructure and devices, and on the other hand if there are investments in Internet infrastructure, there will be economic growth. This resembles the chicken and egg problem. For many African countries, which lack large public investment funds and at the same time suffer from other more important socio-economic challenges, it might be tricky to put effort into Internet policy issues. But there are some good examples of countries that have actually managed to do this, for example Kenya. As a result these efforts can lead to positive effects on the society and economy as a whole. The local context, and a focus on instruments that disseminate Internet usage in unprivileged geographic areas and social groups (like the Universal Service Fund) are very important.

Ed.: How much of the low Internet perpetration in large parts of Africa is simply due to large rural populations—and therefore something that will either never be resolved properly, or that will naturally resolve itself with the ongoing shift to urban centres?

Robert: We did not see a clear causality between rural population and low Internet on a country level, mainly due to the fact that countries with a large rural population are often quite rich and thus also have money to invest in Internet infrastructure. Africa is very dependent on agriculture. Although the Internet connectivity issue might be “self-resolved” to some degree by urban migration, other issues would emerge from such a shift such as an increased socio-economic divide in the urban areas. Hence, it is more effective to make sure that the Internet reaches rural areas at an early stage.

Ed.: And how much does domestic policy (around things like telecoms) get set internally, as opposed to externally? Presumably some things (e.g. the continent-wide cables required to connect Africa to the rest of the world) are easier to bring about if there is a strong / stable regional policy around regulation of markets and competition—whether organised internally, or influenced by outside governments and industry?

Robert: The influence of telecom ministries and telecom operators is strong, but of course they are affected by intra-regional organisations, private companies etc. In the past Africa has had difficulties in developing pan-regional trade and policies. But such initiatives are encouraged, not least in order to facilitate cost-sharing of large Internet-related investments.

Ed.: Leaving aside the question of causality, you mention the strong correlation between economic activity and Internet penetration: are there any African countries that buck this trend—at either end of the economic scale?

Robert: We have seen that Kenya and Nigeria have had quite impressive rates of Internet penetration in relation to GDP. Gabon on the other hand is a relatively rich African country, but with quite low Internet penetration.

Read the full article: Wentrup, R., Xu, X., Nakamura, H.R., and Ström, P. (2016) Crossing the Digital Desert in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does Policy Matter? Policy & Internet 8 (3). doi:10.1002/poi3.123

Robert Wentrup was talking to blog editor David Sutcliffe.