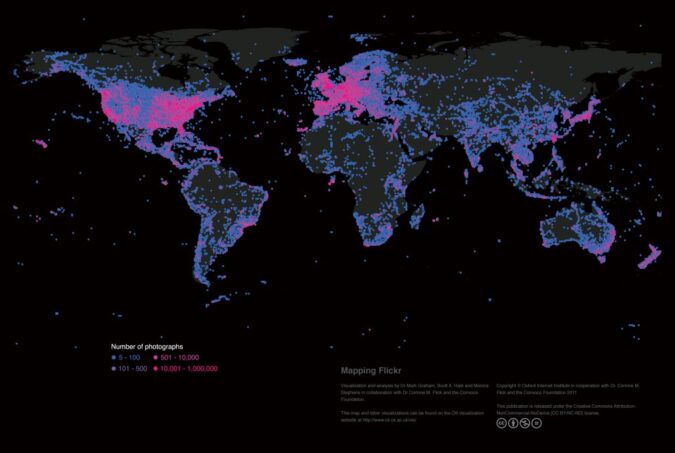

Images are an important form of knowledge that allow us to develop understandings about our world; the global geographic distribution of geotagged images on Flickr reveals the density of visual representations and locally depicted knowledge of all places on our planet. Map by M.Graham, M.Stephens, S.Hale.

Information is the raw material for much of the work that goes on in the contemporary global economy, and visibility and voice in this information ecosystem is a prerequisite for influence and control. As Hand and Sandywell (2002: 199) have argued, “digitalised knowledge and its electronic media are indeed synonymous with power.” As such, it is important to understand who produces and reproduces information, who has access to it, and who and where are represented by it. Traditionally, information and knowledge about the world have been geographically constrained. The transmission of information required either the movement of people or the availability of some other medium of communication. However, up until the late 20th century, almost all mediums of information—books, newspapers, academic journals, patents and the like—were characterised by huge geographic inequalities. The global north produced, consumed and controlled much of the world’s codified knowledge, while the global south was largely left out. Today, the movement of information is, in theory, rarely constrained by distance. Very few parts of the world remain disconnected from the grid, and over 2 billion people are now online (most of them in the Global South). Unsurprisingly, many believe we now have the potential to access what Wikipedia’s founder Jimmy Wales refers to as “the sum of all human knowledge”. Theoretically, parts of the world that have been left out of flows and representations of knowledge can be quite literally put back on the map. However, “potential” has too often been confused with actual practice, and stark digital divisions of labour are still evident in all open platforms that rely on user-generated content. Google Map’s databases contain more indexed user-generated content about the Tokyo metropolitan region than the entire continent of Africa. On Wikipedia, there is more written about Germany than about South America and Africa combined. In other words, there are massive inequalities that cannot simply be explained by uneven Internet penetration. A range of…