All Articles

All topics

-

Experiments are the most exciting thing on the UK public policy horizon

Very few of these experiments use manipulation of information environments on the internet as a…

-

Uncovering the structure of online child exploitation networks

Despite large investments of law enforcement resources, online child exploitation is nowhere near under control,…

-

Searching for a “Plan B”: young adults’ strategies for finding information about emergency contraception online

While the Internet is a valuable source of information about sexual health for young adults,…

-

Understanding low and discontinued Internet use amongst young people in Britain

– in EducationWhy do these people stop using the Internet given its prevalence and value in the…

-

The “IPP2012: Big Data, Big Challenges” conference explores the new research frontiers opened up by big data as well as its limitations

– in ConferencesBig data generation and analysis requires expertise and skills which can be a particular challenge…

-

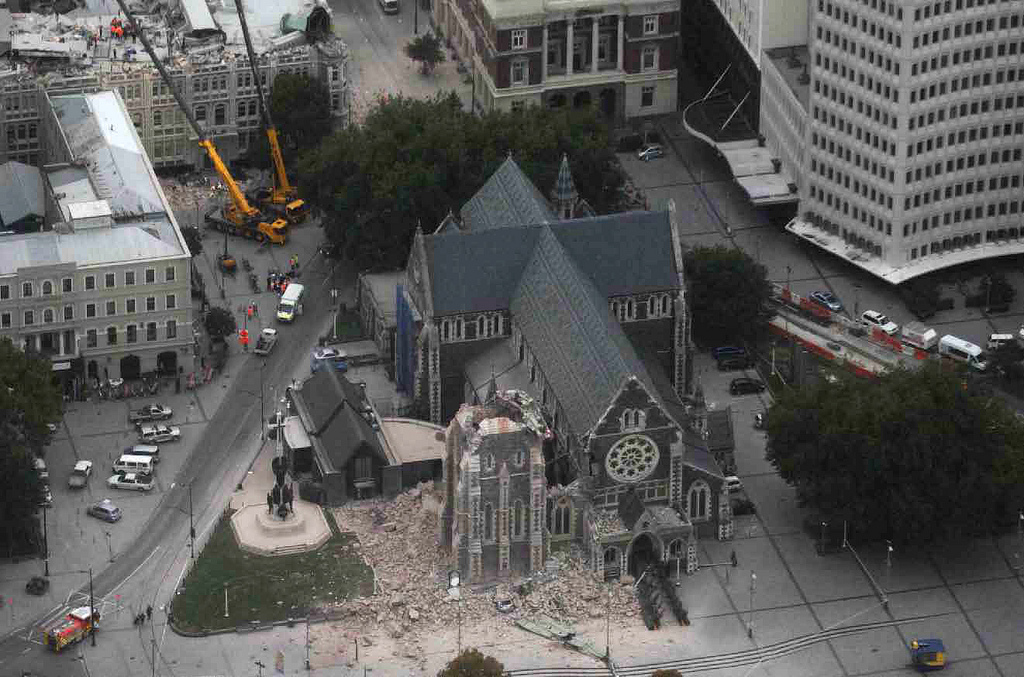

Preserving the digital record of major natural disasters: the CEISMIC Canterbury Earthquakes Digital Archive project

The Internet can be hugely useful to coordinate disaster relief efforts, or to help rebuild…

-

Slicing digital data: methodological challenges in computational social science

Small changes in individual actions can have large effects at the aggregate level; this opens…

-

eHealth: what is needed at the policy level? New special issue from Policy and Internet

Policymakers wishing to promote greater choice and control among health system users should take account…