All Articles

All topics

-

The scramble for Africa’s data

– in DevelopmentAs Africa goes digital, the challenge for policymakers becomes moving from digitisation to managing and…

-

How effective is online blocking of illegal child sexual content?

Combating child pornography and child abuse is a universal and legitimate concern. With regard to…

-

Presenting the moral imperative: effective storytelling strategies by online campaigning organisations

Existing civil society focused organisations are also being challenged to fundamentally change their approach, to…

-

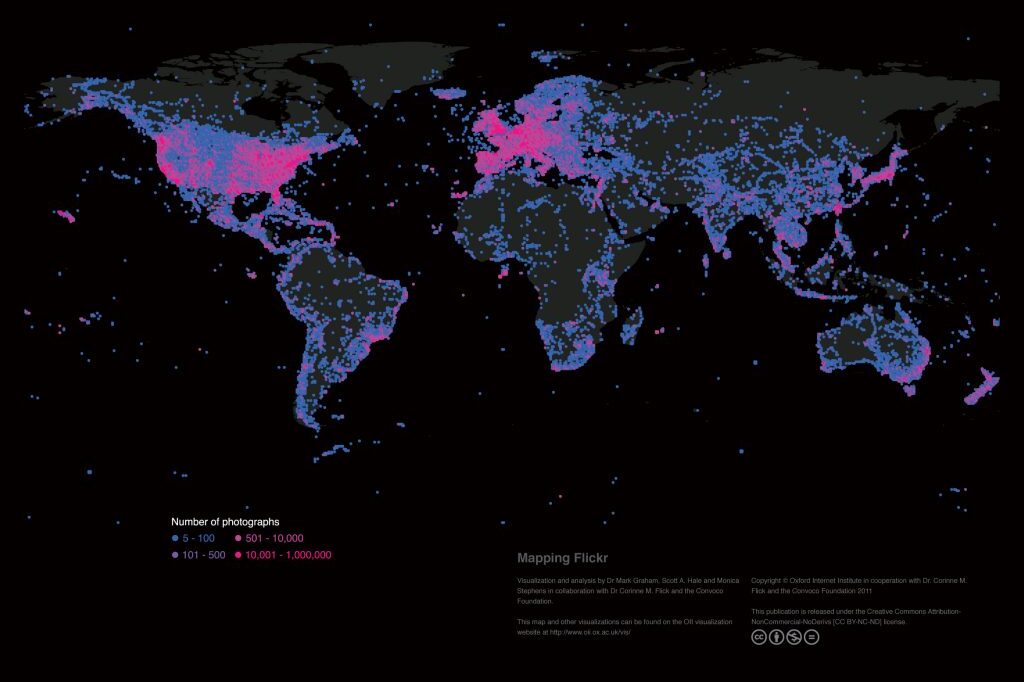

Mapping the uneven geographies of information worldwide

There are massive inequalities that cannot simply be explained by uneven Internet penetration. A range…

-

The global fight over copyright control: Is David beating Goliath at his own game?

We stress the importance of digital environments for providing contenders of copyright reform with a…

-

How accessible are online legislative data archives to political scientists?

Government agencies are rarely completely transparent, often do not provide clear instructions for accessing the…

-

Online crowd-sourcing of scientific data could document the worldwide loss of glaciers to climate change

The platform aims to create long-lasting scientific value with minimal technical entry barriers—it is valuable…

-

Time for debate about the societal impact of the Internet of Things

As the cost and size of devices falls and network access becomes ubiquitous, it is…

-

Online collective action and policy change: shifting contentious politics in policy processes

The Internet can facilitate the involvement of social movements in policymaking processes, but also constitute…