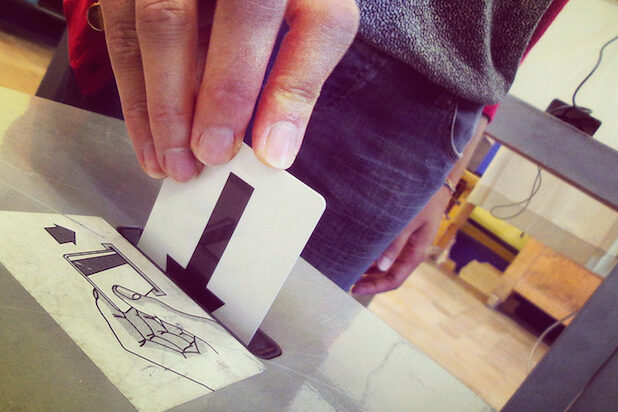

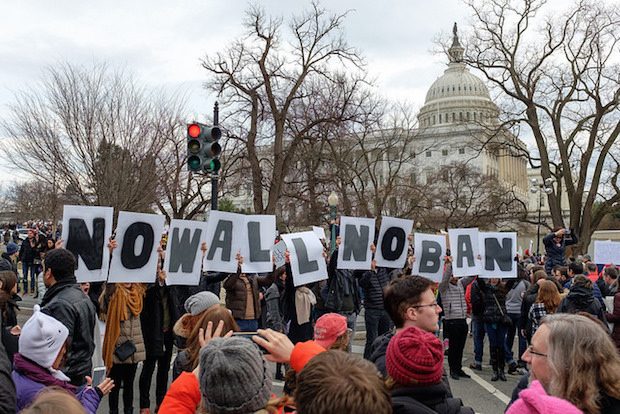

Involving local communities in political decisions is essential for transparent governance. This involvement is especially important in controversial issues, such as the siting of infrastructure, where a balance must be struck between the collective benefits of projects and the personal costs for nearby residents. However, despite efforts to engage communities, participation processes often lead to protests, loss of trust, and project blockades. This is where e-participation tools can play a significant role. As digital transformation reshapes governance, an increasing number of online platforms are being integrated into traditional participation processes. These platforms aim to make participation more inclusive and transparent by allowing individuals to engage regardless of their location or the time and by fostering a space for clear knowledge exchange. Nonetheless, how effective are communities in accessing these tools, particularly when conflicts are already intense? Can e-participation improve policy processes, or do existing conflicts hinder its potential? Our recent article published in Policy & Internet, titled “Digital Citizen Participation in Policy Conflict and Concord: Evaluation of a Web-Based Planning Tool for Railroad Infrastructure” by Ilana Schröder and Nils C. Bandelow, explores these questions. The research examines the performance of e-participation in both low- and high-conflict settings by focusing on a web-based tool that allows citizens to propose alternative railroad routes. Study participants were asked to use the online tool in a hypothetical scenario characterized as either conflictual or consensual. They then assessed the tool’s ability to promote inclusion, transparency, conflict resolution, and efficiency in the decision-making process. Here are the key findings: E-Participation Can Enhance Transparency and Mutual Understanding: Participants in both low- and high-conflict scenarios indicated that digital participation tools help enhance transparency in decision-making processes. When used effectively, these tools clarify planning criteria, include local knowledge, and improve mutual understanding among stakeholders. Therefore, e-participation tools can help reduce conflict escalation and facilitate creative solutions to complex issues. Digital Tools Aren’t a One-Size-Fits-All Solution: While digital platforms have…

Can e-participation improve policy processes, or do existing conflicts hinder its potential?