Tag: big data

All topics

-

Responsible research agendas for public policy in the era of big data

Bringing together leading social science academics with senior government agency staff to discuss its public…

-

Seeing like a machine: big data and the challenges of measuring Africa’s informal economies

– in DevelopmentIn a similar way that economists have traditionally excluded unpaid domestic labour from national accounts,…

-

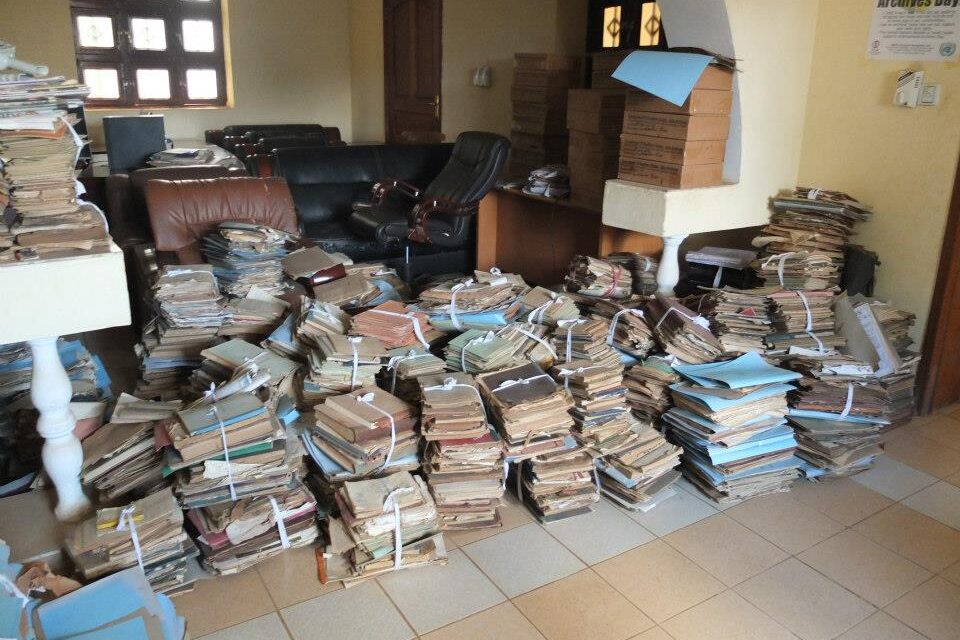

The scramble for Africa’s data

– in DevelopmentAs Africa goes digital, the challenge for policymakers becomes moving from digitisation to managing and…

-

Uncovering the structure of online child exploitation networks

Despite large investments of law enforcement resources, online child exploitation is nowhere near under control,…