Tag: Africa

All topics

-

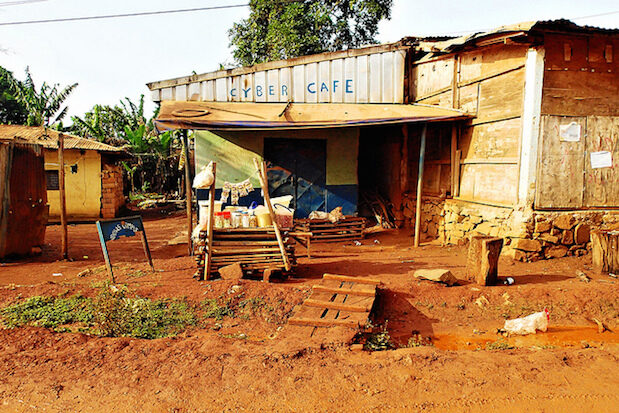

Has Internet policy had any effect on Internet penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa?

It is important for policymakers to ask how policy can bridge economic inequality. But does…

-

Why we shouldn’t believe the hype about the Internet “creating” development

– in DevelopmentDespite the vigour of such claims, there is actually a lack of academic consensus about…

-

Is China shaping the Internet in Africa?

Concerns have been expressed about the detrimental role China may play in African media sectors,…

-

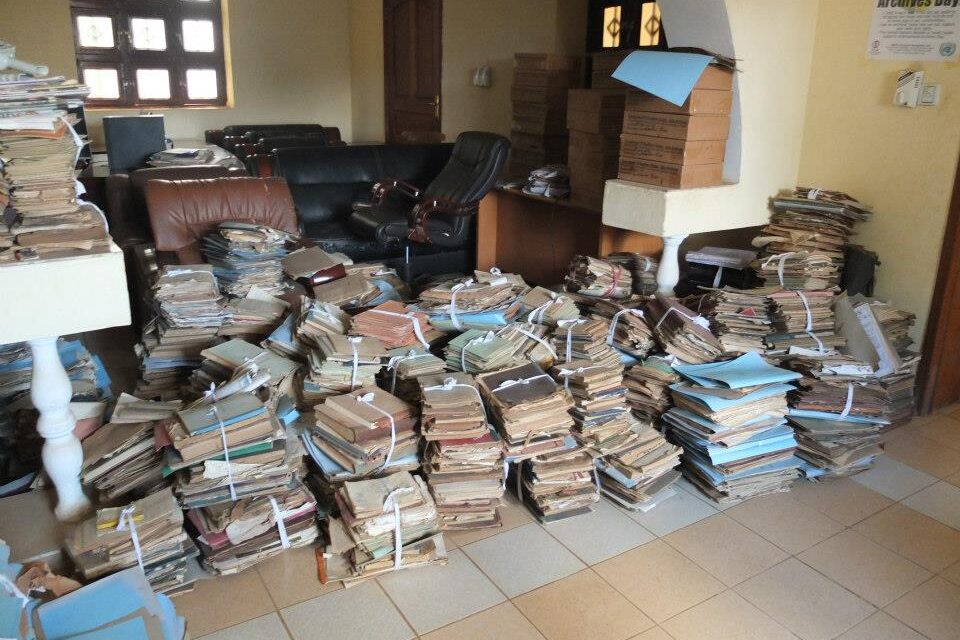

Seeing like a machine: big data and the challenges of measuring Africa’s informal economies

– in DevelopmentIn a similar way that economists have traditionally excluded unpaid domestic labour from national accounts,…