Category: Development

All topics

-

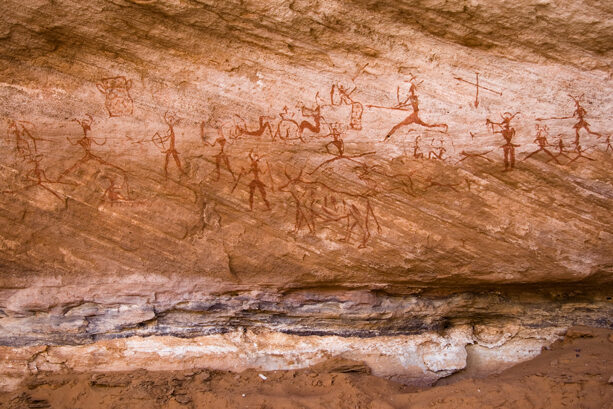

Why global contributions to Wikipedia are so unequal

– in DevelopmentThe geography of knowledge has always been uneven. Some people and places have always been…

-

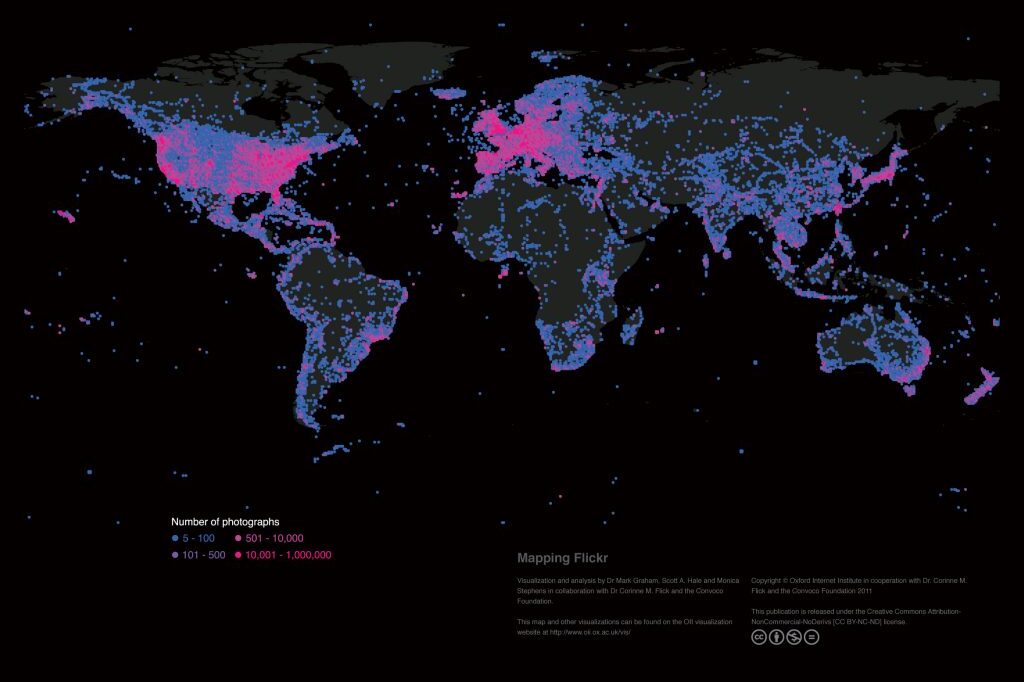

What explains the worldwide patterns in user-generated geographical content?

As geographic content and geospatial information becomes increasingly integral to our everyday lives, places that…

-

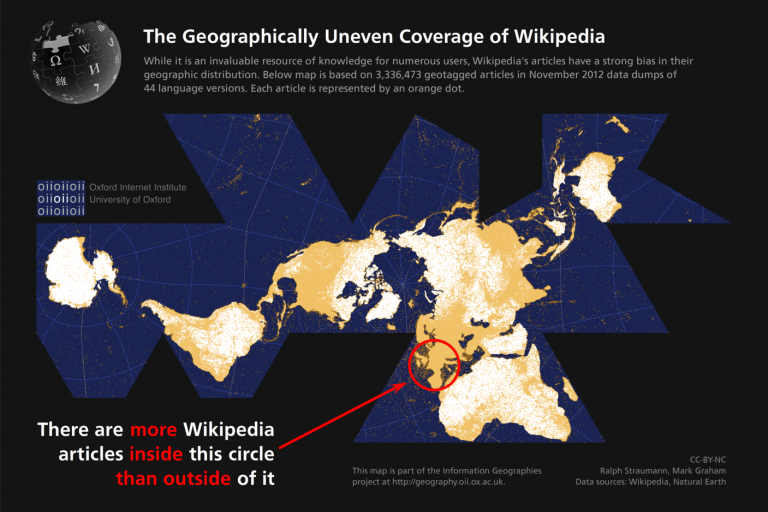

Geotagging reveals Wikipedia is not quite so equal after all

– in DevelopmentWikipedia is often seen as a great equaliser. But it’s starting to look like global…

-

What is stopping greater representation of the MENA region?

Negotiating the wider politics of Wikipedia can be a daunting task, particularly when in it…

-

How well represented is the MENA region in Wikipedia?

There are more Wikipedia articles in English than Arabic about almost every Arabic speaking country…

-

The sum of (some) human knowledge: Wikipedia and representation in the Arab World

Arabic is one of the least represented major world languages on Wikipedia: few languages have…

-

The economic expectations and potentials of broadband Internet in East Africa

Were firms adopting internet, as it became cheaper? Had this new connectivity had the effects…

-

Is China shaping the Internet in Africa?

Concerns have been expressed about the detrimental role China may play in African media sectors,…

-

Seeing like a machine: big data and the challenges of measuring Africa’s informal economies

– in DevelopmentIn a similar way that economists have traditionally excluded unpaid domestic labour from national accounts,…

-

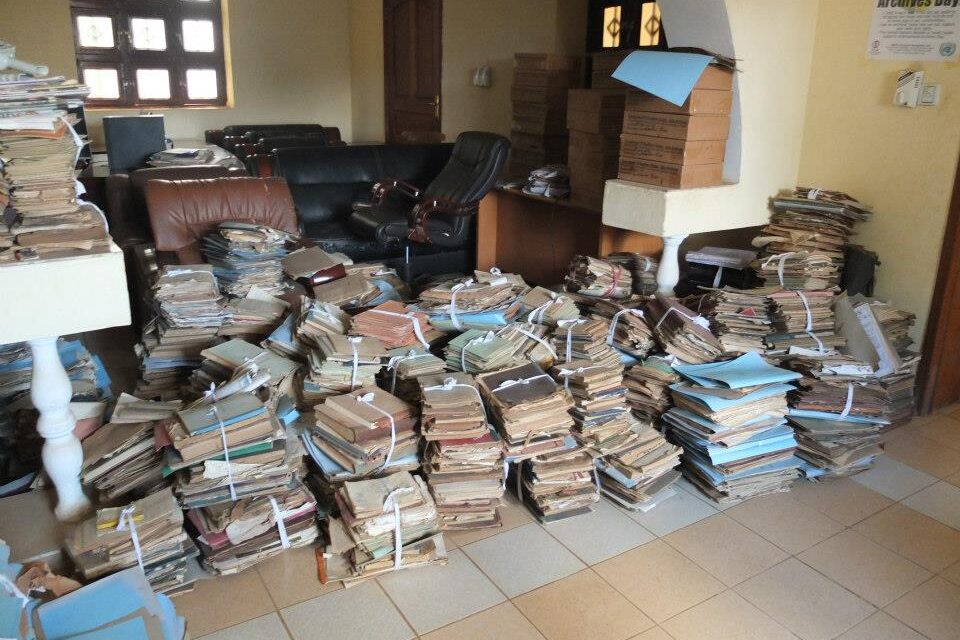

The scramble for Africa’s data

– in DevelopmentAs Africa goes digital, the challenge for policymakers becomes moving from digitisation to managing and…

-

Mapping the uneven geographies of information worldwide

There are massive inequalities that cannot simply be explained by uneven Internet penetration. A range…