All Articles

All topics

-

How and why is children’s digital data being harvested?

It’s time to refocus on our responsibilities to children before they are eclipsed by the commercial…

-

Has Internet policy had any effect on Internet penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa?

It is important for policymakers to ask how policy can bridge economic inequality. But does…

-

How do we encourage greater public inclusion in Internet governance debates?

The Internet is neither purely public nor private, but combines public and private networks, platforms,…

-

We should look to automation to relieve the current pressures on healthcare

Automation may address these pressures in primary care, while also reconfiguring the work of staff…

-

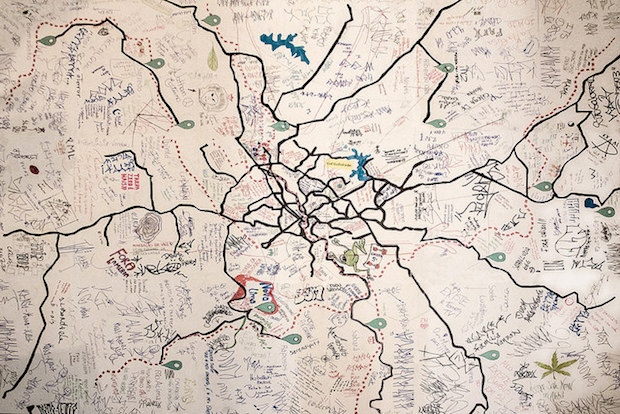

Should citizens be allowed to vote on public budgets?

Considered to be a successful example of empowered democratic governance, participatory budgeting has spread among…

-

Can universal basic income counter the ill-effects of the gig economy?

– in EconomicsBasic income is an interesting solution for the gig economy, because it addresses its problems…

-

Governments Want Citizens to Transact Online: And This Is How to Nudge Them There

Peter John and Toby Blume design and report a randomised control trial that encouraged users…

-

Why we shouldn’t believe the hype about the Internet “creating” development

– in DevelopmentDespite the vigour of such claims, there is actually a lack of academic consensus about…

-

Internet Filtering: And Why It Doesn’t Really Help Protect Teens

– in InterviewsStriking the right balance between protecting adolescents and respecting their rights to freedom of expression…