All Articles

All topics

-

Why we shouldn’t be pathologising online gaming before the evidence is in

– in WellbeingNew study suggests that Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) may not, in itself, be robustly associated…

-

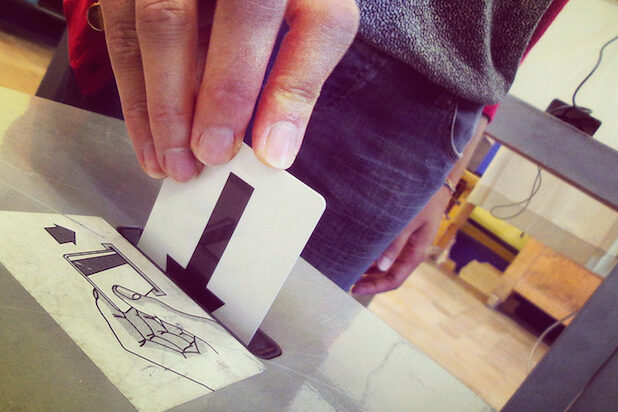

Does Internet voting offer a solution to declining electoral turnout?

While a technological fix probably won’t address the underlying reasons for low turnout, it could…

-

From private profit to public liabilities: how platform capitalism’s business model works for children

– in WellbeingWhy has platform capitalism come to dominate children’s relationship to the internet and why is…

-

Introducing Martin Dittus, Data Scientist and Darknet Researcher

Martin Dittus is a Data Scientist at the Oxford Internet Institute. The stringent ethics process…

-

Exploring the Darknet in Five Easy Questions

– in EconomicsWe caught up with Martin Dittus to find out some basics about darknet markets, and…

-

Digital platforms are governing systems—so it’s time we examined them in more detail

It’s important that we take a multi-perspective view of the role of digital platforms in…

-

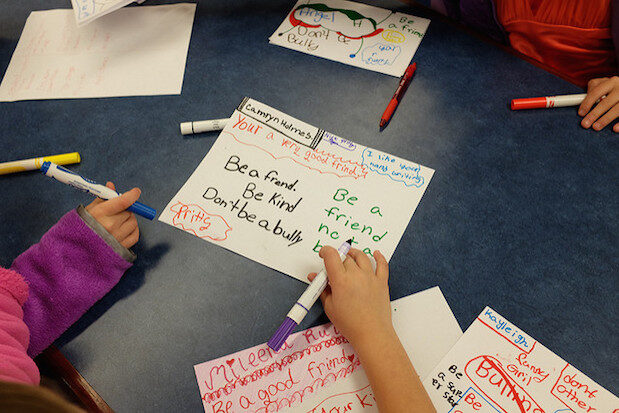

Design ethics for gender-based violence and safety technologies

– in WellbeingSharing instructive primers for developers interested in creating technologies for those affected by gender-based violence.

-

Considering the Taylor Review: Ways Forward for the Gig Economy

– in EconomicsThe review assesses changes in labour markets and employment practices, and proposes policy solutions.

-

Open government policies are spreading across Europe—but what are the expected benefits?

Mapping out the different meanings of open government, and how it is framed by different…

-

Does Twitter now set the news agenda?

Matthew A. Shapiro and Libby Hemphill examine the extent to which he traditional media is…