All Articles

All topics

-

Outside the cities and towns, rural Britain’s internet is firmly stuck in the 20th century

The quality of rural internet access in the UK, or lack of it, has long…

-

Designing Internet technologies for the public good

People are very often unaware of how much data is gathered about them—let alone the…

-

The life and death of political news: using online data to measure the impact of the audience agenda

Editors must now decide not only what to publish and where, but how long it…

-

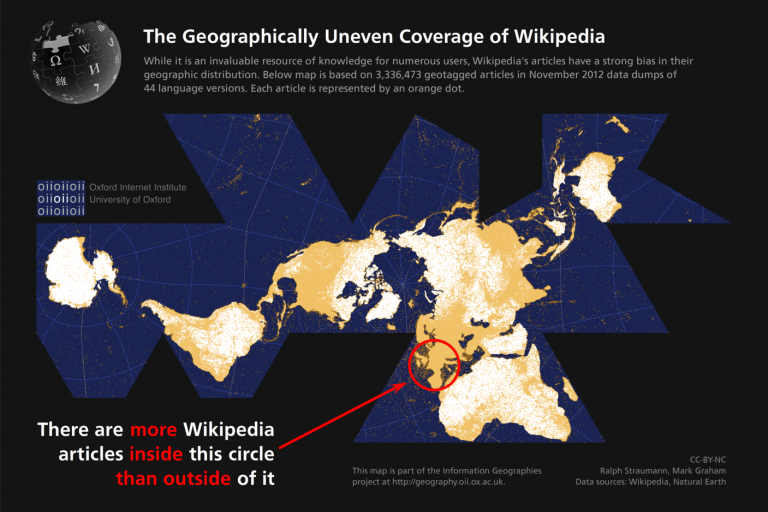

Why global contributions to Wikipedia are so unequal

– in DevelopmentThe geography of knowledge has always been uneven. Some people and places have always been…

-

What explains the worldwide patterns in user-generated geographical content?

As geographic content and geospatial information becomes increasingly integral to our everyday lives, places that…

-

Geotagging reveals Wikipedia is not quite so equal after all

– in DevelopmentWikipedia is often seen as a great equaliser. But it’s starting to look like global…

-

Monitoring Internet openness and rights: report from the Citizen Lab Summer Institute 2014

Informing the global discussions on information control research and practice in the fields of censorship,…

-

What is stopping greater representation of the MENA region?

Negotiating the wider politics of Wikipedia can be a daunting task, particularly when in it…

-

Evidence on the extent of harms experienced by children as a result of online risks: implications for policy and research

If we only undertake research on the nature or extent of risk, then it’s difficult…

-

How well represented is the MENA region in Wikipedia?

There are more Wikipedia articles in English than Arabic about almost every Arabic speaking country…