Standing on a stage in San Francisco in early 2010, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, partly responding to the site’s decision to change the privacy settings of its 350 million users, announced that as Internet users had become more comfortable sharing information online, privacy was no longer a “social norm”. Of course, he had an obvious commercial interest in relaxing norms surrounding online privacy, but this attitude has nevertheless been widely echoed in the popular media. Young people are supposed to be sharing their private lives online—and providing huge amounts of data for commercial and government entities—because they don’t fully understand the implications of the public nature of the Internet.

There has actually been little systematic research on the privacy behaviour of different age groups in online settings. But there is certainly evidence of a growing (general) concern about online privacy (Marwick et al., 2010), with a 2013 Pew study finding that 50 percent of Internet users were worried about the information available about them online, up from 30 percent in 2009. Following the recent revelations about the NSA’s surveillance activities, a Washington Post-ABC poll reported 40 percent of its U.S. respondents as saying that it was more important to protect citizens’ privacy even if it limited the ability of the government to investigate terrorist threats. But what of young people, specifically? Do they really care less about their online privacy than older users?

Privacy concerns an individual’s ability to control what personal information about them is disclosed, to whom, when, and under what circumstances. We present different versions of ourselves to different audiences, and the expectations and norms of the particular audience (or context) will determine what personal information is presented or kept hidden. This highlights a fundamental problem with privacy in some SNSs: that of ‘context collapse’ (Marwick and boyd 2011). This describes what happens when audiences that are normally kept separate offline (such as employers and family) collapse into a single online context: such a single Facebook account or Twitter channel. This could lead to problems when actions that are appropriate in one context are seen by members of another audience; consider for example, the US high school teacher who was forced to resign after a parent complained about a Facebook photo of her holding a glass of wine while on holiday in Europe.

SNSs are particularly useful for investigating how people handle privacy. Their tendency to collapse the “circles of social life” may prompt users to reflect more about their online privacy (particularly if they have been primed by media coverage of people losing their jobs, going to prison, etc. as a result of injudicious postings). However, despite SNS being an incredibly useful source of information about online behaviour practices, few articles in the large body of literature on online privacy draw on systematically collected data, and the results published so far are probably best described as conflicting (see the literature review in the full paper). Furthermore, they often use convenience samples of college students, meaning they are unable to adequately address either age effects, or potentially related variables such as education and income. These ambiguities certainly provide fertile ground for additional research; particularly research based on empirical data.

The OII’s own Oxford Internet Surveys (OxIS) collect data on British Internet users and non-users through nationally representative random samples of more than 2,000 individuals aged 14 and older, surveyed face-to-face. One of the (many) things we are interested in is online privacy behaviour, which we measure by asking respondents who have an SNS profile: “Thinking about all the social network sites you use, on average how often do you check or change your privacy settings?” In addition to the demographic factors we collect about respondents (age, sex, location, education, income etc.), we can construct various non-demographic measures that might have a bearing on this question, such as: comfort revealing personal data; bad experiences online; concern with negative experiences; number of SNSs used; and self-reported ability using the Internet.

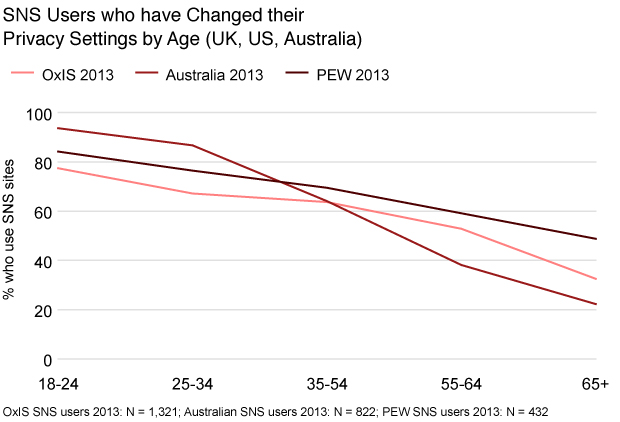

So are young people completely unconcerned about their privacy online, gaily granting access to everything to everyone? Well, in a word, no. We actually find a clear inverse relationship: almost 95% of 14-17-year-olds have checked or changed their SNS privacy settings, with the percentage steadily dropping to 32.5% of respondents aged 65 and over. The strength of this effect is remarkable: between the oldest and youngest the difference is over 62 percentage points, and we find little difference in the pattern between the 2013 and 2011 surveys. This immediately suggests that the common assumption that young people don’t care about—and won’t act on—privacy concerns is probably wrong.

Comparing our own data with recent nationally representative surveys from Australia (OAIC 2013) and the US (Pew 2013) we see an amazing similarity: young people are more, not less, likely to have taken action to protect the privacy of their personal information on social networking sites than older people. We find that this age effect remains significant even after controlling for other demographic variables (such as education). And none of the five non-demographic variables changes the age effect either (see the paper for the full data, analysis and modelling). The age effect appears to be real.

So in short, and contrary to the prevailing discourse, we do not find young people to be apathetic when it comes to online privacy. Barnes (2006) outlined the original ‘privacy paradox’ by arguing that “adults are concerned about invasion of privacy, while teens freely give up personal information (…) because often teens are not aware of the public nature of the Internet.” This may once have been true, but it is certainly not the case today.

Existing theories are unable to explain why young people are more likely to act to protect privacy, but maybe the answer lies in the broad, fundamental characteristics of social life. It is social structure that creates context: people know each other based around shared life stages, experiences and purposes. Every person is the centre of many social circles, and different circles have different norms for what is acceptable behaviour, and thus for what is made public or kept private. If we think of privacy as a sort of meta-norm that arises between groups rather than within groups, it provides a way to smooth out some of the inevitable conflicts of the varied contexts of modern social life.

This might help explain why young people are particularly concerned about their online privacy. At a time when they’re leaving their families and establishing their own identities, they will often be doing activities in one circle (e.g. friends) that they do not want known in other circles (e.g. potential employers or parents). As an individual enters the work force, starts to pay taxes, and develops friendships and relationships farther from the home, the number of social circles increases, increasing the potential for conflicting privacy norms. Of course, while privacy may still be a strong social norm, it may not be in the interest of the SNS provider to cater for its differentiated nature.

The real paradox is that these sites have become so embedded in the social lives of users that to maintain their social lives they must disclose information on them despite the fact that there is a significant privacy risk in disclosing this information; and often inadequate controls to help users to meet their diverse and complex privacy needs.

Read the full paper: Blank, G., Bolsover, G., and Dubois, E. (2014) A New Privacy Paradox: Young people and privacy on social network sites. Prepared for the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, 16-19 August 2014, San Francisco, California.

References

Barnes, S. B. (2006). A privacy paradox: Social networking in the United States. First Monday,11(9).

Marwick, A. E., Murgia-Diaz, D., & Palfrey, J. G. (2010). Youth, Privacy and Reputation (Literature Review). SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1588163. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

Marwick, A. E., & boyd, D. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114–133. doi:10.1177/1461444810365313

Grant Blank is a Survey Research Fellow at the OII. He is a sociologist who studies the social and cultural impact of the Internet and other new communication media.