Tag: labour

All topics

-

Considering the Taylor Review: Ways Forward for the Gig Economy

– in EconomicsThe review assesses changes in labour markets and employment practices, and proposes policy solutions.

-

We should look to automation to relieve the current pressures on healthcare

Automation may address these pressures in primary care, while also reconfiguring the work of staff…

-

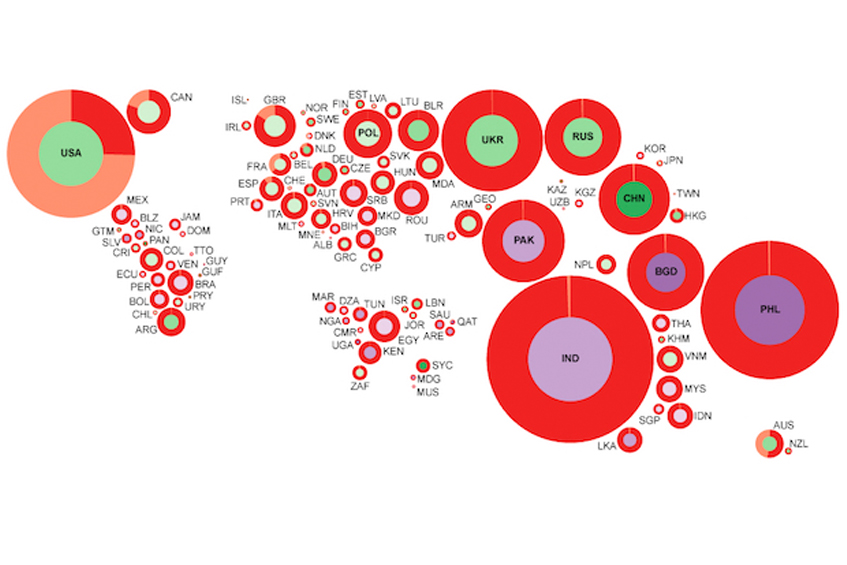

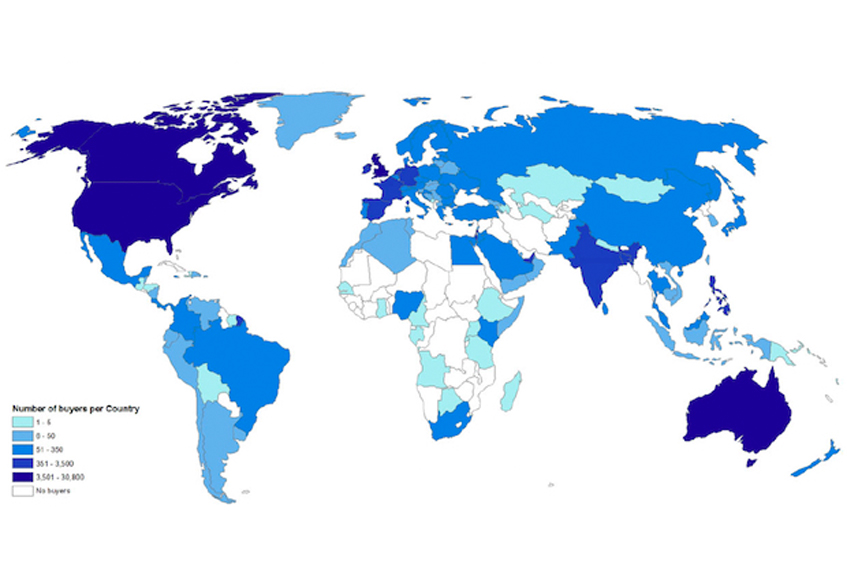

New Report: Risks and Rewards of Online Gig Work at the Global Margins

– in DevelopmentThe report poses questions for all stakeholders regarding how to improve the conditions and livelihoods…

-

What Impact is the Gig Economy Having on Development and Worker Livelihoods?

– in DevelopmentReflecting on some of the key benefits and costs associated with these new digital regimes…

-

Investigating virtual production networks in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia

This mass connectivity has been one crucial ingredient for some significant changes in how work…