Changes in the ways knowledge is created and used are driving economic and social development worldwide. Ugandan school by Brian Wolfe (Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0).

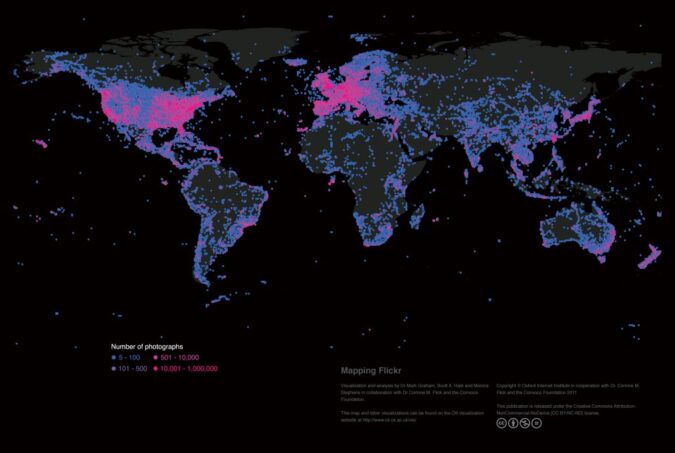

“In times past, we searched for gold, precious stones, minerals, and ore. Today, it is knowledge that makes us rich and access to information is all-powerful in enabling individual and collective success.” Lesotho Ministry of Communications, Science and Technology, 2005. Changes in the ways knowledge is created and used—and how this is enabled by new information technologies—are driving economic and social development worldwide. Discussions of the “knowledge economy” see knowledge both as an economic output in itself, and as an input that strengthens economic processes; with developing countries tending to be described as planning or embarking on a journey of transformation into knowledge economies to bring about economic gain. Indeed, increasing connectivity has sparked many hopes for the democratisation of knowledge production in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite the centrality of digital connectivity to the knowledge economy, there are few studies of the geographies of digital knowledge and information. In their article “Engagement in the Knowledge Economy: Regional Patterns of Content Creation with a Focus on Sub-Saharan Africa”, published in Information Technologies & International Development, Sanna Ojanperä, Mark Graham, Ralph K. Straumann, Stefano De Sabbata, and Matthew Zook investigate the patterns of knowledge creation in the region. They examine three key metrics: spatial distributions of academic articles (i.e. traditional knowledge production), collaborative software development, and Internet domain registrations (i.e. digitally mediated knowledge production). Contrary to expectations, they find distribution patterns of digital content (measured by collaborative coding and domain registrations) to be more geographically uneven than those of academic articles: despite the hopes for the democratising power of the information revolution. This suggests that the factors often framed as catalysts for a knowledge economy do not relate to these three metrics uniformly. Connectivity is an important enabler of digital content creation, but it seems to be only a necessary, not a sufficient, condition; wealth, innovation capacity, and public spending on education are also important factors. While the growth in telecommunications might be…