Tag: governance

All topics

-

The blockchain paradox: Why distributed ledger technologies may do little to transform the economy

Applying elementary institutional economics to examine what blockchain technologies really do in terms of economic…

-

New Voluntary Code: Guidance for Sharing Data Between Organisations

For data sharing between organisations to be straight forward, there needs to a common understanding…

-

Crowdsourcing ideas as an emerging form of multistakeholder participation in Internet governance

Assessing the extent to which crowdsourcing represents an emerging opportunity of participation in global public…

-

Uber and Airbnb make the rules now — but to whose benefit?

Outlining a more nuanced theory of institutional change that suggests that platforms’ effects on society…

-

Why are citizens migrating to Uber and Airbnb, and what should governments do about it?

What if we dug into existing social science theory to see what it has to…

-

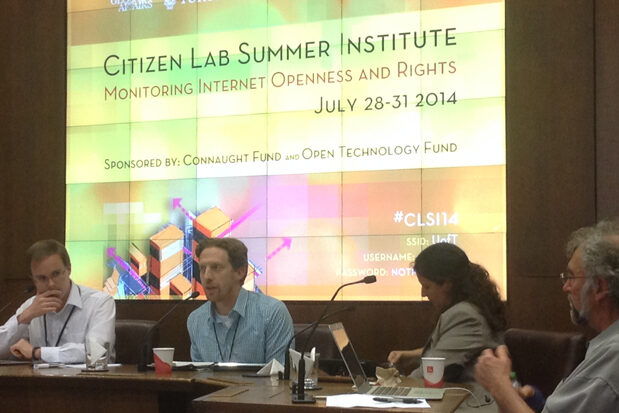

Monitoring Internet openness and rights: report from the Citizen Lab Summer Institute 2014

Informing the global discussions on information control research and practice in the fields of censorship,…

-

The complicated relationship between Chinese Internet users and their government

Chinese citizens are being encouraged by the government to engage and complain online. Is the…

-

Chinese Internet users share the same values concerning free speech, privacy, and control as their Western counterparts

Many people—even in China—see the Internet as a tool for free speech and as a…

-

Is China changing the Internet, or is the Internet changing China?

By 2015, the proportion of Chinese language Internet users is expected to exceed the proportion…