Tag: data

All topics

-

From private profit to public liabilities: how platform capitalism’s business model works for children

– in WellbeingWhy has platform capitalism come to dominate children’s relationship to the internet and why is…

-

How and why is children’s digital data being harvested?

It’s time to refocus on our responsibilities to children before they are eclipsed by the commercial…

-

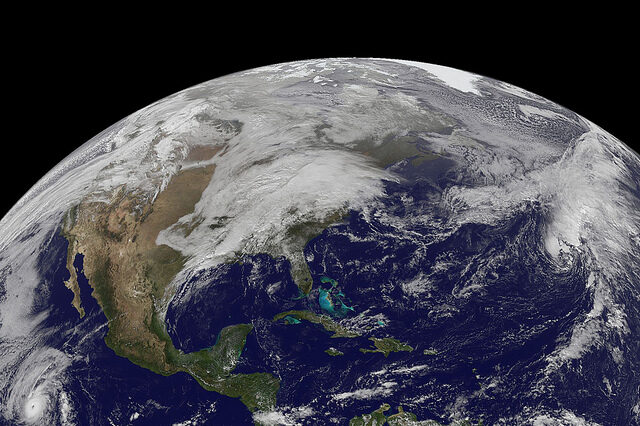

Could data pay for global development? Introducing data financing for global good

Are there ways in which the data economy could directly finance global causes such as…

-

New Voluntary Code: Guidance for Sharing Data Between Organisations

For data sharing between organisations to be straight forward, there needs to a common understanding…

-

Can drones, data and digital technology provide answers to nature conservation challenges?

– in EnvironmentDrone technology for conservation purposes is new, and its cost effectiveness—when compared with other kinds…

-

Unpacking patient trust in the “who” and the “how” of Internet-based health records

Key to successful adoption of Internet-based health records is how much a patient places trust…

-

The challenges of government use of cloud services for public service delivery

One central concern of those governments that are leading in the public sector’s migration to…