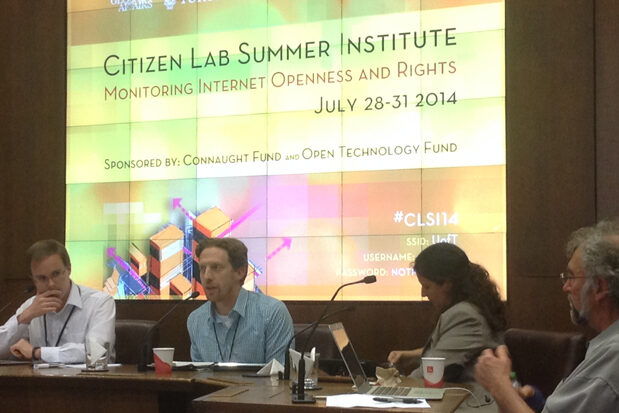

根据相关法律法规和政策,部分搜索结果未予显示 could be a warning message we will see displayed more often on the Internet; but likely translations thereof. In Chinese, this means “according to the relevant laws, regulations, and policies, a portion of search results have not been displayed.” The control of information flows on the Internet is becoming more commonplace, in authoritarian regimes as well as in liberal democracies, either via technical or regulatory means. Such information controls can be defined as “[…] actions conducted in or through information and communications technologies (ICTs), which seek to deny (such as web filtering), disrupt (such as denial-of-service attacks), shape (such as throttling), secure (such as through encryption or circumvention) or monitor (such as passive or targeted surveillance) information for political ends. Information controls can also be non-technical and can be implemented through legal and regulatory frameworks, including informal pressures placed on private companies. […]” Information controls are not intrinsically good or bad, but much is to be explored and analysed about their use, for political or commercial purposes. The University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab organised a one-week summer institute titled “Monitoring Internet Openness and Rights” to inform the global discussions on information control research and practice in the fields of censorship, circumvention, surveillance and adherence to human rights. A week full of presentations and workshops on the intersection of technical tools, social science research, ethical and legal reflections and policy implications was attended by a distinguished group of about 60 community members, amongst whom were two OII DPhil students; Jon Penney and Ben Zevenbergen. Conducting Internet measurements may be considered to be a terra incognita in terms of methodology and data collection, but the relevance and impacts for Internet policy-making, geopolitics or network management are obvious and undisputed. The Citizen Lab prides itself in being a “hacker hothouse”, or an “intelligence agency for civil society” where security expertise, politics, and ethics intersect. Their research adds the much-needed geopolitical angle to…

Informing the global discussions on information control research and practice in the fields of censorship, circumvention, surveillance and adherence to human rights.