Category: Wellbeing

All topics

-

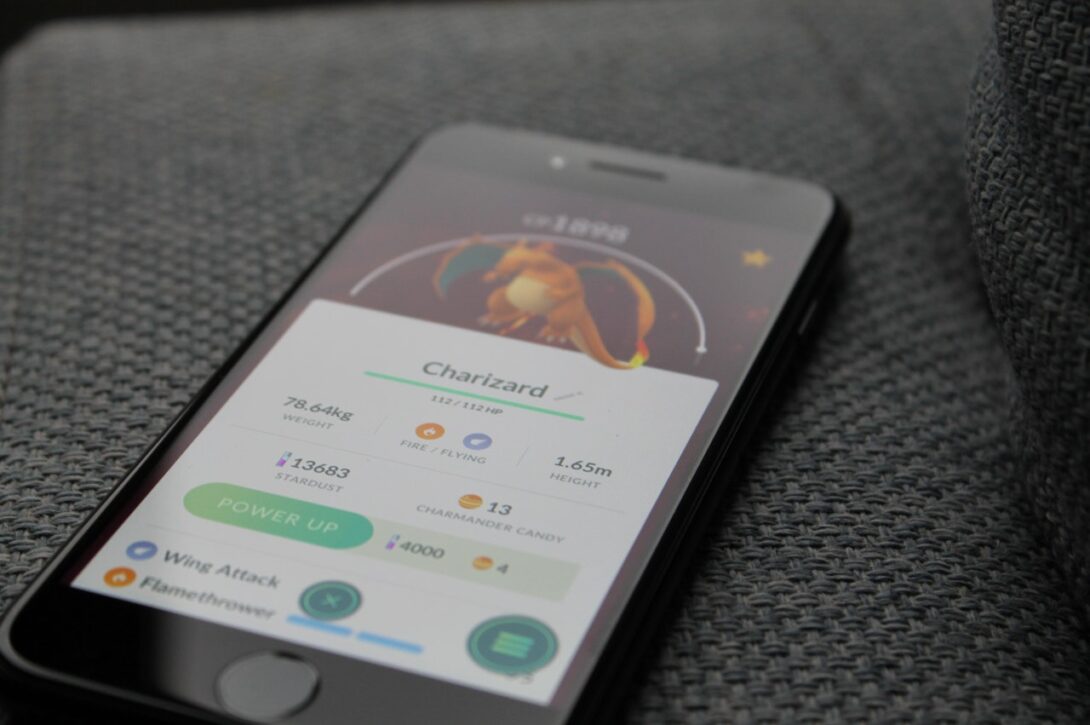

Why we shouldn’t be pathologising online gaming before the evidence is in

– in WellbeingNew study suggests that Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) may not, in itself, be robustly associated…

-

From private profit to public liabilities: how platform capitalism’s business model works for children

– in WellbeingWhy has platform capitalism come to dominate children’s relationship to the internet and why is…

-

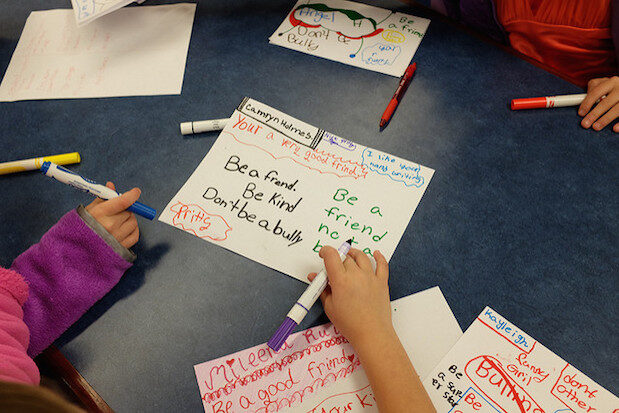

Design ethics for gender-based violence and safety technologies

– in WellbeingSharing instructive primers for developers interested in creating technologies for those affected by gender-based violence.

-

Social media is nothing like drugs, despite all the horror stories

– in WellbeingIn reality, social media can have both positive and negative outcomes.

-

How and why is children’s digital data being harvested?

It’s time to refocus on our responsibilities to children before they are eclipsed by the commercial…

-

We should look to automation to relieve the current pressures on healthcare

Automation may address these pressures in primary care, while also reconfiguring the work of staff…

-

Psychology is in Crisis: And Here’s How to Fix It

It seems that in psychology and communication, as in other fields of social science, much…

-

Tackling Digital Inequality: Why We Have to Think Bigger

While the UK government has financed technological infrastructure and invested in schemes to address digital…

-

Five Pieces You Should Probably Read On: Reality, Augmented Reality and Ambient Fun

Things you should probably know, and things that deserve to be brought out for another…

-

Exploring the world of digital detoxing

Advocates of “digital detoxing” view digital communication as eroding our ability to concentrate, to empathise,…