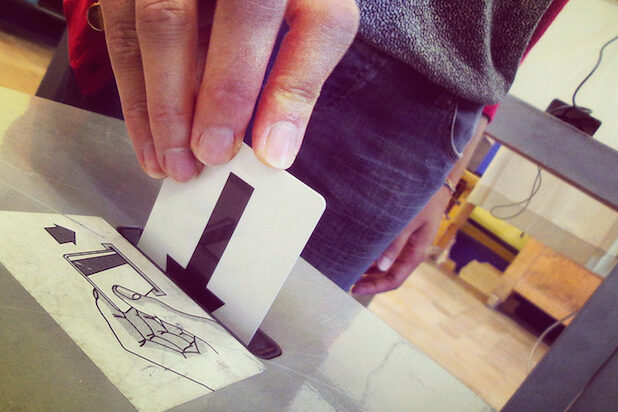

Þingvellir: location of the Althing, the national parliament of Iceland, established in 930 AD with sessions held at the location until 1798. Image: Luc Van Braekel (Flickr CC BY 2.0).

As innovations like social media and open government initiatives have become an integral part of politics in the twenty-first century, there is increasing interest in the possibility of citizens directly participating in the drafting of legislation. Indeed, there is a clear trend of greater public participation in the process of constitution making, and with the growth of e-democracy tools, this trend is likely to continue. However, this view is certainly not universally held, and a number of recent studies have been much more skeptical about the value of public participation, questioning whether it has any real impact on the text of a constitution. Following the banking crisis, and a groundswell of popular opposition to the existing political system in 2009, the people of Iceland embarked on a unique process of constitutional reform. Having opened the entire drafting process to public input and scrutiny, these efforts culminated in Iceland’s 2011 draft crowdsourced constitution: reputedly the world’s first. In his Policy & Internet article “When Does Public Participation Make a Difference? Evidence From Iceland’s Crowdsourced Constitution”, Alexander Hudson examines the impact that the Icelandic public had on the development of the draft constitution. He finds that almost 10 percent of the written proposals submitted generated a change in the draft text, particularly in the area of rights. This remarkably high number is likely explained by the isolation of the drafters from both political parties and special interests, making them more reliant on and open to input from the public. However, although this would appear to be an example of successful public crowdsourcing, the new constitution was ultimately rejected by parliament. Iceland’s experiment with participatory drafting therefore demonstrates the possibility of successful online public engagement — but also the need to connect the masses with the political elites. It was the disconnect between these groups that triggered the initial protests and constitutional reform, but also that led to its ultimate failure. We caught…