Category: Politics & Government

All topics

-

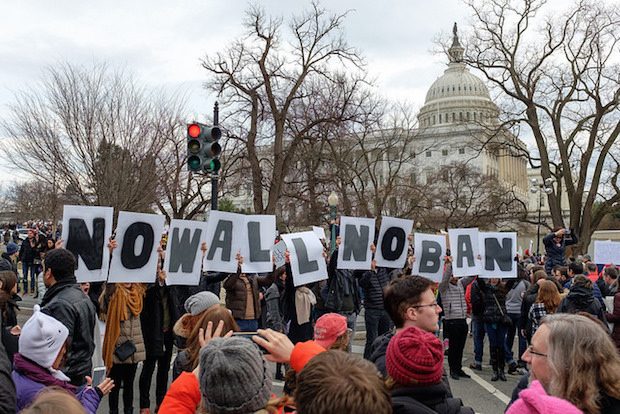

How can we encourage participation in online political deliberation?

The Internet seems to provide an obvious opportunity to strengthen intra-party democracy and mobilise passive…

-

Making crowdsourcing work as a space for democratic deliberation

Is crowdsourcing conducive to deliberation among citizens or is it essentially just a consulting mechanism…

-

Habermas by design: designing public deliberation into online platforms

What particular platform features should we look to, to promote deliberative debate online?

-

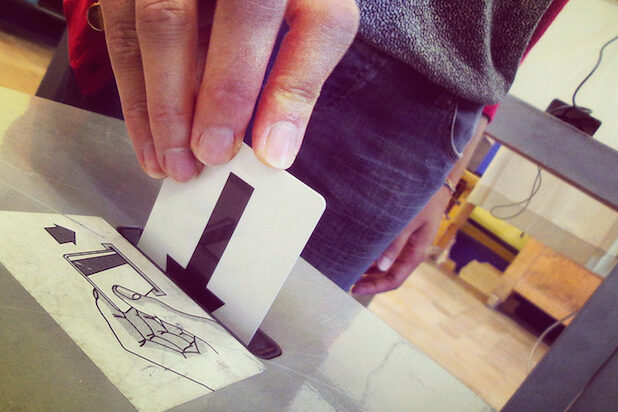

Does Internet voting offer a solution to declining electoral turnout?

While a technological fix probably won’t address the underlying reasons for low turnout, it could…

-

Open government policies are spreading across Europe—but what are the expected benefits?

Mapping out the different meanings of open government, and how it is framed by different…

-

Does Twitter now set the news agenda?

Matthew A. Shapiro and Libby Hemphill examine the extent to which he traditional media is…

-

What explains variation in online political engagement?

Examining the supply of channels for digital politics distributed by Swedish municipalities and understanding the…

-

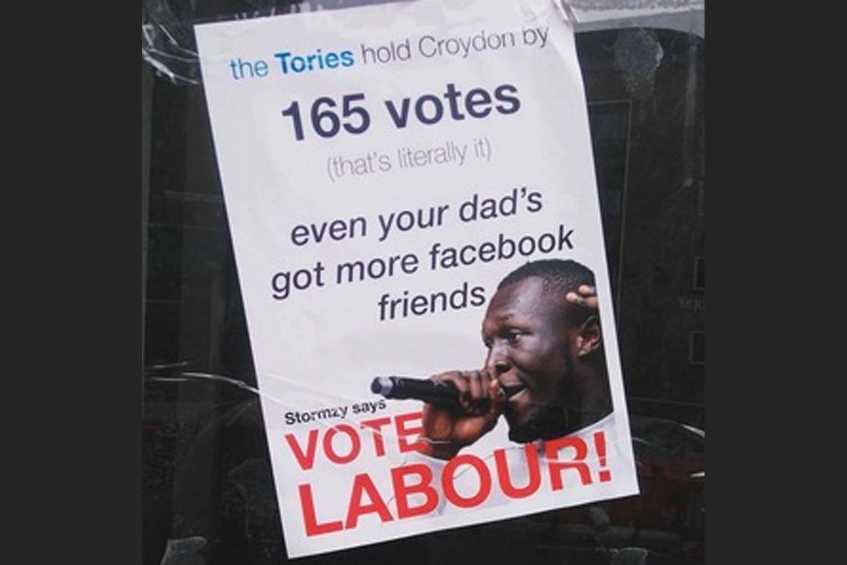

Stormzy 1: The Sun 0—Three Reasons Why #GE2017 Was the Real Social Media Election

It could be the first election where the right wing tabloids finally ceded their influence…

-

Could Voting Advice Applications force politicians to keep their manifesto promises?

A number of studies have shown that VAA use has an impact on the cognitive…

-

Using Open Government Data to predict sense of local community

Advocates hope that opening government data will increase government transparency, catalyse economic growth, address social…

-

Is Left-Right still meaningful in politics? Or are we all just winners or losers of globalisation now?

The Left–Right dimension is the most common way of conceptualising ideological difference. But in an…