Category: Governance & Security

All topics

-

Crowdsourcing ideas as an emerging form of multistakeholder participation in Internet governance

Assessing the extent to which crowdsourcing represents an emerging opportunity of participation in global public…

-

Using Wikipedia as PR is a problem, but our lack of a critical eye is worse

That Wikipedia is used for less-than scrupulously neutral purposes shouldn’t surprise us – our lack…

-

Uber and Airbnb make the rules now — but to whose benefit?

Outlining a more nuanced theory of institutional change that suggests that platforms’ effects on society…

-

Why are citizens migrating to Uber and Airbnb, and what should governments do about it?

What if we dug into existing social science theory to see what it has to…

-

Iris scanners can now identify us from 40 feet away

Public anxiety and legal protections currently pose a major challenge to anyone wanting to introduce…

-

Should we use old or new rules to regulate warfare in the information age?

Information has now acquired a pivotal role in contemporary warfare, for it has become both…

-

Does a market-approach to online privacy protection result in better protection for users?

Examining the voluntary provision by commercial sites of information privacy protection and control under the…

-

Will digital innovation disintermediate banking—and can regulatory frameworks keep up?

The role of finance in enabling the development and implementation of new ideas is vital—an…

-

Designing Internet technologies for the public good

People are very often unaware of how much data is gathered about them—let alone the…

-

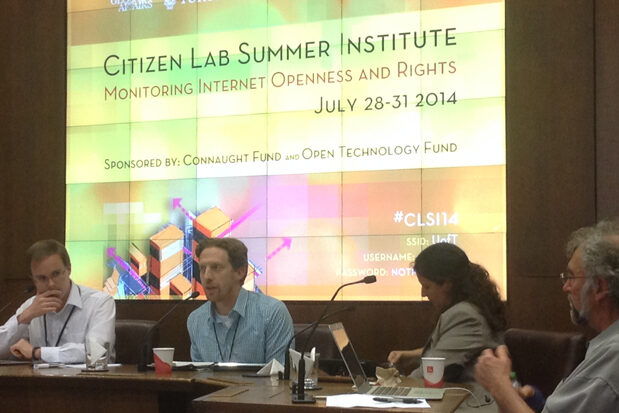

Monitoring Internet openness and rights: report from the Citizen Lab Summer Institute 2014

Informing the global discussions on information control research and practice in the fields of censorship,…

-

Evidence on the extent of harms experienced by children as a result of online risks: implications for policy and research

If we only undertake research on the nature or extent of risk, then it’s difficult…