Author: Mark Graham

All topics

-

New Report: Risks and Rewards of Online Gig Work at the Global Margins

– in DevelopmentThe report poses questions for all stakeholders regarding how to improve the conditions and livelihoods…

-

What Impact is the Gig Economy Having on Development and Worker Livelihoods?

– in DevelopmentReflecting on some of the key benefits and costs associated with these new digital regimes…

-

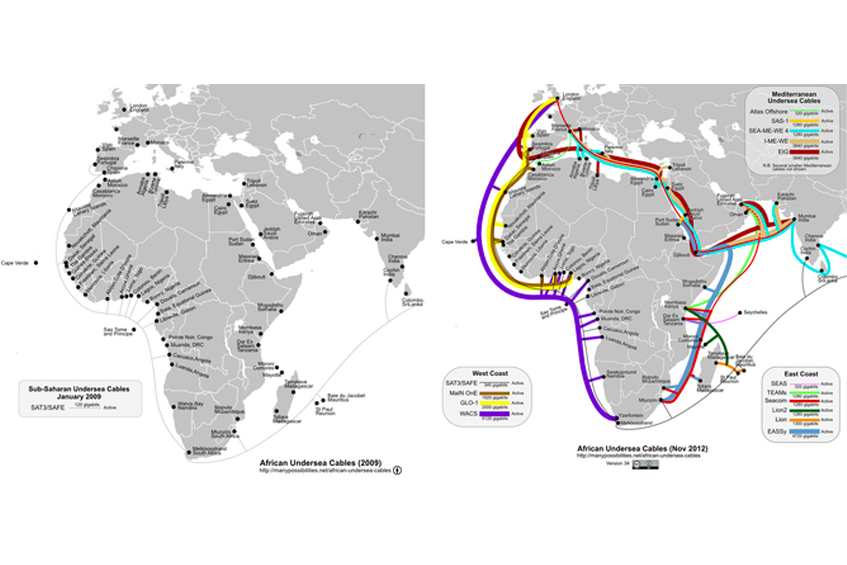

Broadband may be East Africa’s 21st century railway to the world

The excitement over the potentially transformative effects of the internet in low-income countries is nowhere…

-

Investigating virtual production networks in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia

This mass connectivity has been one crucial ingredient for some significant changes in how work…

-

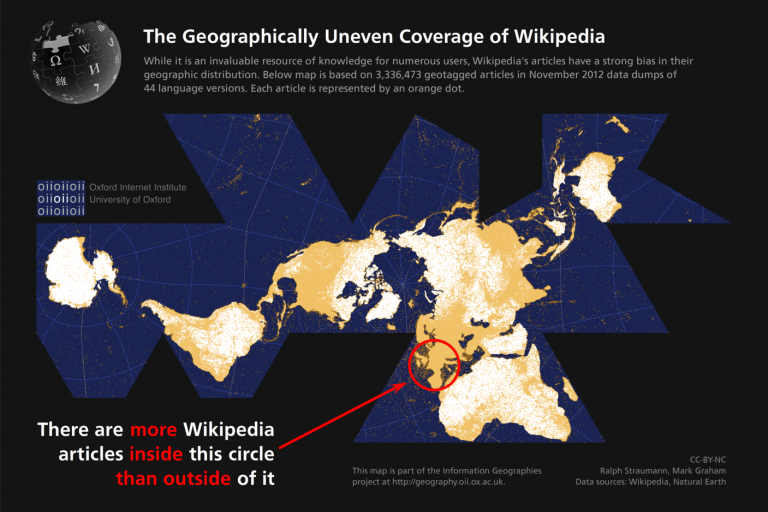

Why global contributions to Wikipedia are so unequal

– in DevelopmentThe geography of knowledge has always been uneven. Some people and places have always been…

-

What explains the worldwide patterns in user-generated geographical content?

As geographic content and geospatial information becomes increasingly integral to our everyday lives, places that…

-

Geotagging reveals Wikipedia is not quite so equal after all

– in DevelopmentWikipedia is often seen as a great equaliser. But it’s starting to look like global…

-

What is stopping greater representation of the MENA region?

Negotiating the wider politics of Wikipedia can be a daunting task, particularly when in it…

-

How well represented is the MENA region in Wikipedia?

There are more Wikipedia articles in English than Arabic about almost every Arabic speaking country…

-

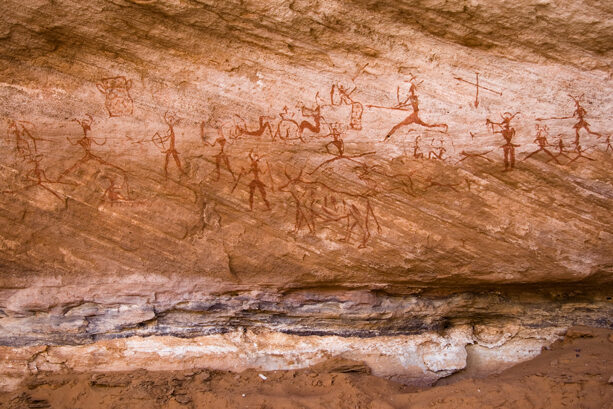

The sum of (some) human knowledge: Wikipedia and representation in the Arab World

Arabic is one of the least represented major world languages on Wikipedia: few languages have…