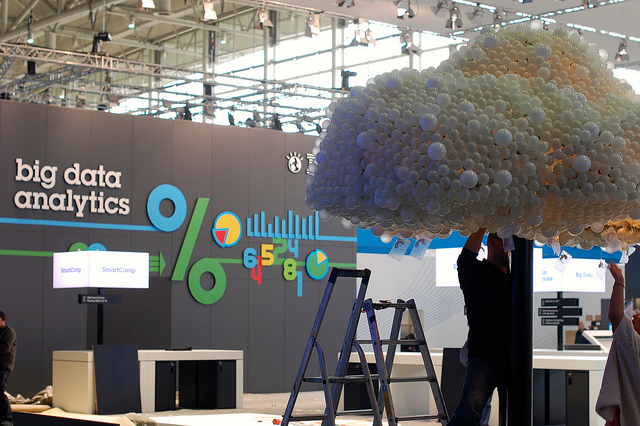

There is a lot of excitement about 'big data', but the potential for innovative work on social and cultural topics far outstrips current data collection and analysis techniques. Image by IBM Deutschland.

Using anything digital always creates a trace. The more digital ‘things’ we interact with, from our smart phones to our programmable coffee pots, the more traces we create. When collected together these traces become big data. These collections of traces can become so large that they are difficult to store, access and analyse with today’s hardware and software. But as a social scientist I’m interested in how this kind of information might be able to illuminate something new about societies, communities, and how we interact with one another, rather than engineering challenges. Social scientists are just beginning to grapple with the technical, ethical, and methodological challenges that stand in the way of this promised enlightenment. Most of us are not trained to write database queries or regular expressions, or even to communicate effectively with those who are trained. Ethical questions arise with informed consent when new analytics are created. Even a data scientist could not know the full implications of consenting to data collection that may be analysed with currently unknown techniques. Furthermore, social scientists tend to specialise in a particular type of data and analysis, surveys or experiments and inferential statistics, interviews and discourse analysis, participant observation and ethnomethodology, and so on. Collaborating across these lines is often difficult, particularly between quantitative and qualitative approaches. Researchers in these areas tend to ask different questions and accept different kinds of answers as valid. Yet trace data does not fit into the quantitative/qualitative binary. The trace of a tweet includes textual information, often with links or images and metadata about who sent it, when and sometimes where they were. The traces of web browsing are also largely textual with some audio/visual elements. The quantity of these textual traces often necessitates some kind of initial quantitative filtering, but it doesn’t determine the questions or approach. The challenges are important to understand and address because the promise of new insight into social life…