All Articles

All topics

-

Why we shouldn’t believe the hype about the Internet “creating” development

– in DevelopmentDespite the vigour of such claims, there is actually a lack of academic consensus about…

-

Internet Filtering: And Why It Doesn’t Really Help Protect Teens

– in InterviewsStriking the right balance between protecting adolescents and respecting their rights to freedom of expression…

-

Psychology is in Crisis: And Here’s How to Fix It

It seems that in psychology and communication, as in other fields of social science, much…

-

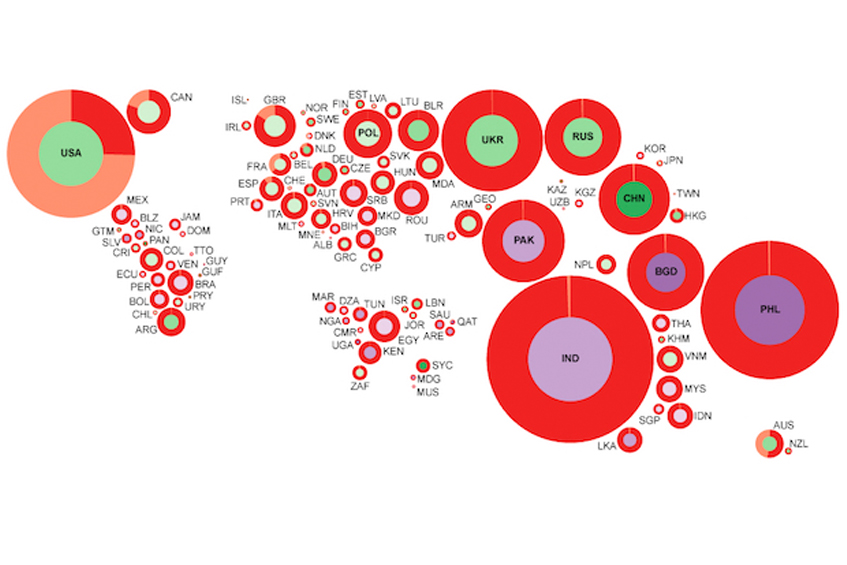

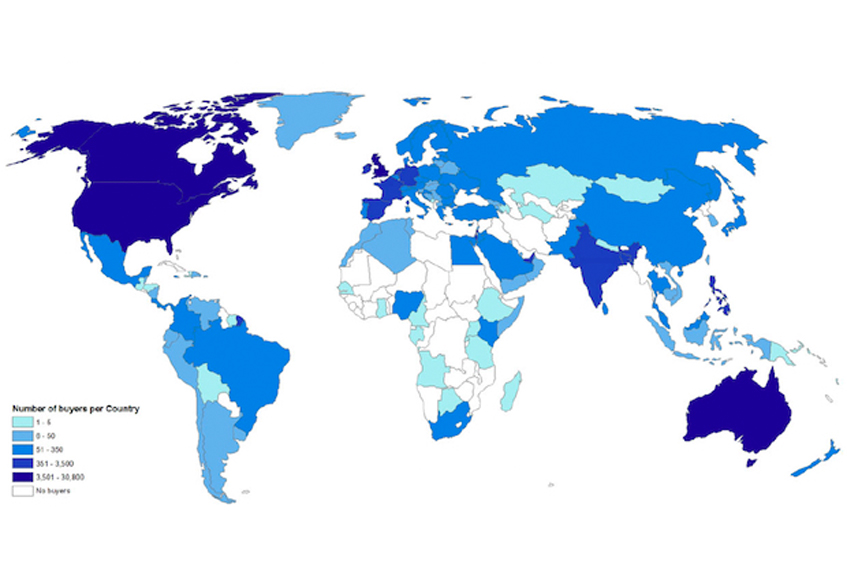

New Report: Risks and Rewards of Online Gig Work at the Global Margins

– in DevelopmentThe report poses questions for all stakeholders regarding how to improve the conditions and livelihoods…

-

What Impact is the Gig Economy Having on Development and Worker Livelihoods?

– in DevelopmentReflecting on some of the key benefits and costs associated with these new digital regimes…

-

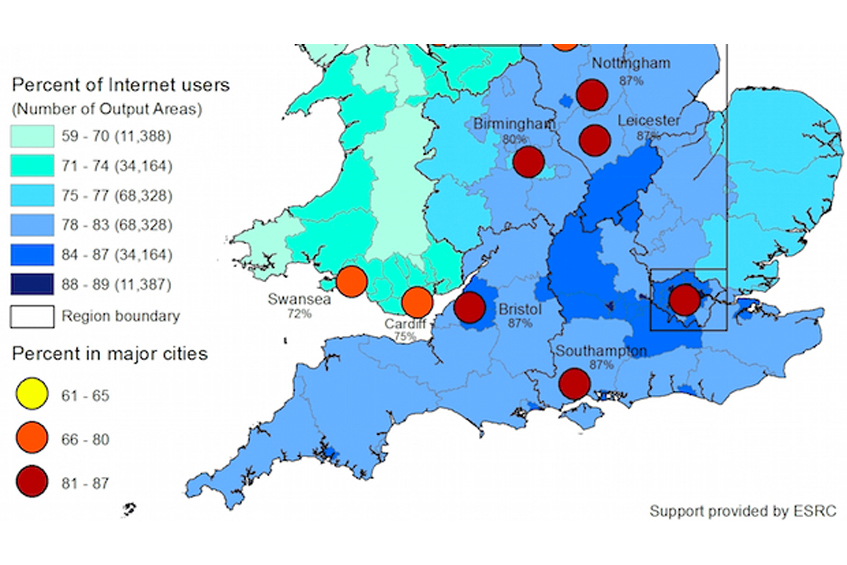

Tackling Digital Inequality: Why We Have to Think Bigger

While the UK government has financed technological infrastructure and invested in schemes to address digital…

-

Five Pieces You Should Probably Read On: Reality, Augmented Reality and Ambient Fun

Things you should probably know, and things that deserve to be brought out for another…

-

Exploring the world of digital detoxing

Advocates of “digital detoxing” view digital communication as eroding our ability to concentrate, to empathise,…

-

“If you’re on Twitter then you’re asking for it”—responses to sexual harassment online and offline

– in WellbeingExploring what sorts of reactions people might have to examples of assault and how they…