All Articles

All topics

-

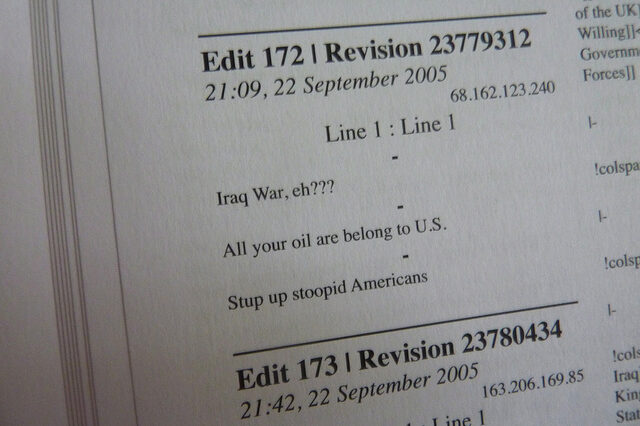

Harnessing ‘generative friction’: can conflict actually improve quality in open systems?

The more that differing points of view and differing evaluative frames came into contact, the…

-

Uncovering the patterns and practice of censorship in Chinese news sites

Is censorship of domestic news more geared towards “avoiding panics and maintaining social order”, or…

-

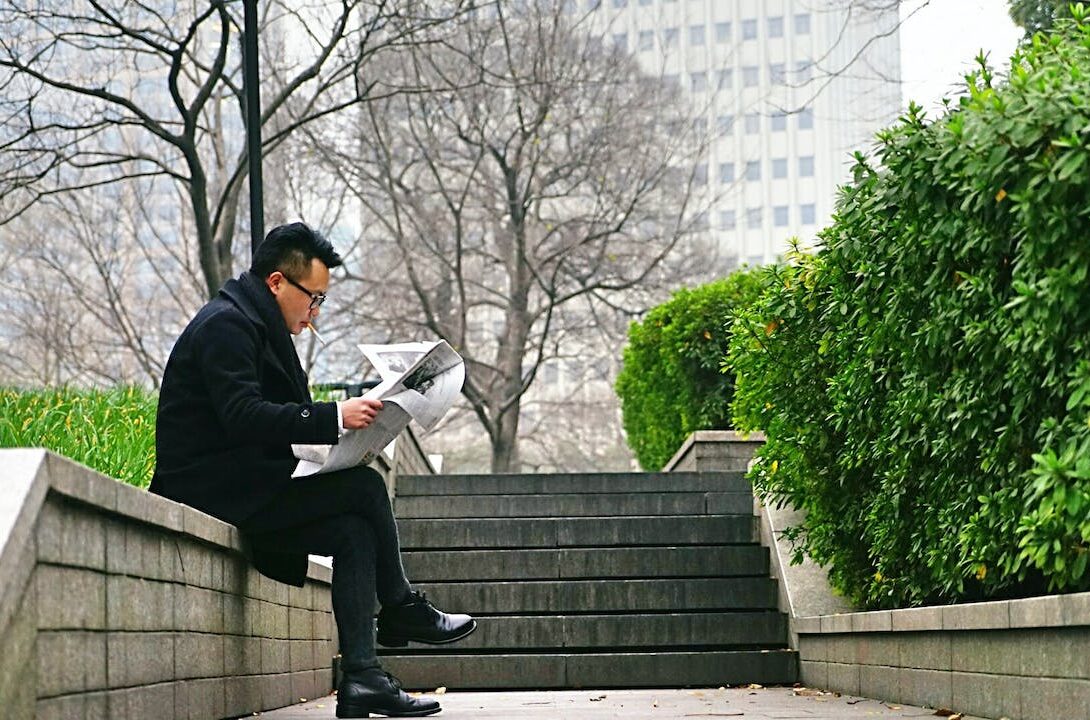

The complicated relationship between Chinese Internet users and their government

Chinese citizens are being encouraged by the government to engage and complain online. Is the…

-

Staying free in a world of persuasive technologies

Broadly speaking, most of the online services we think we’re using for “free”—that is, the…

-

How are internal monitoring systems being used to tackle corruption in the Chinese public administration?

China has made concerted efforts to reduce corruption at the lowest levels of government, as…

-

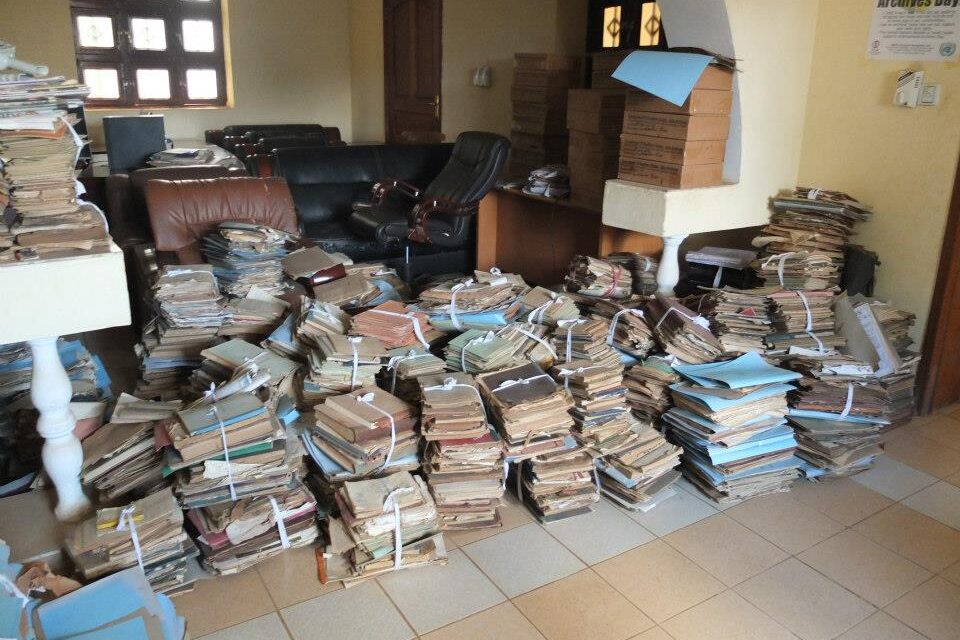

Seeing like a machine: big data and the challenges of measuring Africa’s informal economies

– in DevelopmentIn a similar way that economists have traditionally excluded unpaid domestic labour from national accounts,…

-

Chinese Internet users share the same values concerning free speech, privacy, and control as their Western counterparts

Many people—even in China—see the Internet as a tool for free speech and as a…

-

Is China changing the Internet, or is the Internet changing China?

By 2015, the proportion of Chinese language Internet users is expected to exceed the proportion…

-

The scramble for Africa’s data

– in DevelopmentAs Africa goes digital, the challenge for policymakers becomes moving from digitisation to managing and…

-

How effective is online blocking of illegal child sexual content?

Combating child pornography and child abuse is a universal and legitimate concern. With regard to…

-

Presenting the moral imperative: effective storytelling strategies by online campaigning organisations

Existing civil society focused organisations are also being challenged to fundamentally change their approach, to…