After Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, 2016 will be remembered as the year of cataclysmic democratic events on both sides of the Atlantic. Social media has been implicated in the wave of populism that led to both these developments.

Attention has focused on echo chambers, with many arguing that social media users exist in ideological filter bubbles, narrowly focused on their own preferences, prey to fake news and political bots, reinforcing polarisation and leading voters to turn away from the mainstream. Mark Zuckerberg has responded with the strange claim that his company (built on $5 billion of advertising revenue) does not influence people’s decisions.

So what role did social media play in the political events of 2016?

Political turbulence and the new populism

There is no doubt that social media has brought change to politics. From the waves of protest and unrest in response to the 2008 financial crisis, to the Arab spring of 2011, there has been a generalised feeling that political mobilisation is on the rise, and that social media had something to do with it.

Our book investigating the relationship between social media and collective action, Political Turbulence, focuses on how social media allows new, “tiny acts” of political participation (liking, tweeting, viewing, following, signing petitions and so on), which turn social movement theory around. Rather than identifying with issues, forming collective identity and then acting to support the interests of that identity—or voting for a political party that supports it—in a social media world, people act first, and think about it, or identify with others later, if at all.

These tiny acts of participation can scale up to large-scale mobilisations, such as demonstrations, protests or campaigns for policy change. But they almost always don’t. The overwhelming majority (99.99%) of petitions to the UK or US governments fail to get the 100,000 signatures required for a parliamentary debate (UK) or an official response (US).

The very few that succeed do so very quickly on a massive scale (petitions challenging the Brexit and Trump votes immediately shot above 4 million signatures, to become the largest petitions in history), but without the normal organisational or institutional trappings of a social or political movement, such as leaders or political parties—the reason why so many of the Arab Spring revolutions proved disappointing.

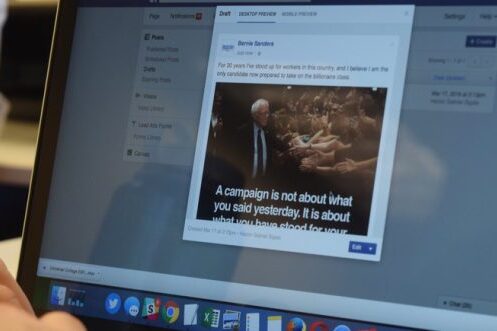

This explosive rise, non-normal distribution and lack of organisation that characterises contemporary politics can explain why many political developments of our time seem to come from nowhere. It can help to understand the shock waves of support that brought us the Italian Five Star Movement, Podemos in Spain, Jeremy Corbyn, Bernie Sanders, and most recently Brexit and Trump—all of which have campaigned against the “establishment” and challenged traditional political institutions to breaking point.

Each successive mobilisation has made people believe that challengers from outside the mainstream are viable—and that is in part what has brought us unlikely results on both sides of the Atlantic. But it doesn’t explain everything.

We’ve had waves of populism before—long before social media (indeed many have made parallels between the politics of 2016 and that of the 1930s). While claims that social media feeds are the biggest threat to democracy, leading to the “disintegration of the general will” and “polarisation that drives populism” abound, hard evidence is more difficult to find.

The myth of the echo chamber

The mechanism that is most often offered for this state of events is the existence of echo chambers or filter bubbles. The argument goes that first social media platforms feed people the news that is closest to their own ideological standpoint (estimated from their previous patterns of consumption) and second, that people create their own personalised information environments through their online behaviour, selecting friends and news sources that back up their world view.

Once in these ideological bubbles, people are prey to fake news and political bots that further reinforce their views. So, some argue, social media reinforces people’s current views and acts as a polarising force on politics, meaning that “random exposure to content is gone from our diets of news and information”.

Really? Is exposure less random than before? Surely the most perfect echo chamber would be the one occupied by someone who only read the Daily Mail in the 1930s—with little possibility of other news—or someone who just watches Fox News? Can our new habitat on social media really be as closed off as these environments, when our digital networks are so very much larger and more heterogeneous than anything we’ve had before?

Research suggests not. A recent large-scale survey (of 50,000 news consumers in 26 countries) shows how those who do not use social media on average come across news from significantly fewer different online sources than those who do. Social media users, it found, receive an additional “boost” in the number of news sources they use each week, even if they are not actually trying to consume more news. These findings are reinforced by an analysis of Facebook data, where 8.8 billion posts, likes and comments were posted through the US election.

Recent research published in Science shows that algorithms play less of a role in exposure to attitude-challenging content than individuals’ own choices and that “on average more than 20% of an individual’s Facebook friends who report an ideological affiliation are from the opposing party”, meaning that social media exposes individuals to at least some ideologically cross-cutting viewpoints: “24% of the hard content shared by liberals’ friends is cross-cutting, compared to 35% for conservatives” (the equivalent figures would be 40% and 45% if random).

In fact, companies have no incentive to create hermetically sealed (as I have heard one commentator claim) echo chambers. Most of social media content is not about politics (sorry guys)—most of that £5 billion advertising revenue does not come from political organisations. So any incentives that companies have to create echo chambers—for the purposes of targeted advertising, for example—are most likely to relate to lifestyle choices or entertainment preferences, rather than political attitudes.

And where filter bubbles do exist they are constantly shifting and sliding —easily punctured by a trending cross-issue item (anybody looking at #Election2016 shortly before polling day would have seen a rich mix of views, while having little doubt about Trump’s impending victory).

And of course, even if political echo chambers were as efficient as some seem to think, there is little evidence that this is what actually shapes election results. After all, by definition echo chambers preach to the converted. It is the undecided people who (for example) the Leave and Trump campaigns needed to reach.

And from the research, it looks like they managed to do just that. A barrage of evidence suggests that such advertising was effective in the 2015 UK general election (where the Conservatives spent 10 times as much as Labour on Facebook advertising), in the EU referendum (where the Leave campaign also focused on paid Facebook ads) and in the presidential election, where Facebook advertising has been credited for Trump’s victory, while the Clinton campaign focused on TV ads. And of course, advanced advertising techniques might actually focus on those undecided voters from their conversations. This is not the bottom-up political mobilisation that fired off support for Podemos or Bernie Sanders. It is massive top-down advertising dollars.

Ironically however, these huge top-down political advertising campaigns have some of the same characteristics as the bottom-up movements discussed above, particularly sustainability. Former New York Governor Mario Cuomo’s dictum that candidates “campaign in poetry and govern in prose” may need an update. Barack Obama’s innovative campaigns of online social networks, micro-donations and matching support were miraculous, but the extent to which he developed digital government or data-driven policy-making in office was disappointing. Campaign digitally, govern in analogue might be the new mantra.

Chaotic pluralism

Politics is a lot messier in the social media era than it used to be—whether something takes off and succeeds in gaining critical mass is far more random than it appears to be from a casual glance, where we see only those that succeed.

In Political Turbulence, we wanted to identify the model of democracy that best encapsulates politics intertwined with social media. The dynamics we observed seem to be leading us to a model of “chaotic pluralism”, characterised by diversity and heterogeneity—similar to early pluralist models – but also by non-linearity and high interconnectivity, making liberal democracies far more disorganised, unstable and unpredictable than the architects of pluralist political thought ever envisaged.

Perhaps rather than blaming social media for undermining democracy, we should be thinking about how we can improve the (inevitably major) part that it plays.

Within chaotic pluralism, there is an urgent need for redesigning democratic institutions that can accommodate new forms of political engagement, and respond to the discontent, inequalities and feelings of exclusion—even anger and alienation—that are at the root of the new populism. We should be using social media to listen to (rather than merely talk at) the expression of these public sentiments, and not just at election time.

Many political institutions—for example, the British Labour Party, the US Republican Party, and the first-past-the-post electoral system shared by both countries—are in crisis, precisely because they have become so far removed from the concerns and needs of citizens. Redesign will need to include social media platforms themselves, which have rapidly become established as institutions of democracy and will be at the heart of any democratic revival.

As these platforms finally start to admit to being media companies (rather than tech companies), we will need to demand human intervention and transparency over algorithms that determine trending news; factchecking (where Google took the lead); algorithms that detect fake news; and possibly even “public interest” bots to counteract the rise of computational propaganda.

Meanwhile, the only thing we can really predict with certainty is that unpredictable things will happen and that social media will be part of our political future.

Discussing the echoes of the 1930s in today’s politics, the Wall Street Journal points out how Roosevelt managed to steer between the extremes of left and right because he knew that “public sentiments of anger and alienation aren’t to be belittled or dismissed, for their causes can be legitimate and their consequences powerful.” The path through populism and polarisation may involve using the opportunity that social media presents to listen, understand and respond to these sentiments.

This piece draws on research from Political Turbulence: How Social Media Shape Collective Action (Princeton University Press, 2016), by Helen Margetts, Peter John, Scott Hale and Taha Yasseri.

It is cross-posted from the World Economic Forum, where it was first published on 22 December 2016.