Category: Economics

All topics

-

Should we love Uber and Airbnb or protest against them?

– in EconomicsSome theorists suggest that such platforms are making our world more efficient by natural selection.…

-

Uber and Airbnb make the rules now — but to whose benefit?

Outlining a more nuanced theory of institutional change that suggests that platforms’ effects on society…

-

Why are citizens migrating to Uber and Airbnb, and what should governments do about it?

What if we dug into existing social science theory to see what it has to…

-

A promised ‘right’ to fast internet rings hollow for millions stuck with 20th-century speeds

Tell those living in the countryside about the government’s promised “right to fast internet” and…

-

Does a market-approach to online privacy protection result in better protection for users?

Examining the voluntary provision by commercial sites of information privacy protection and control under the…

-

Will digital innovation disintermediate banking—and can regulatory frameworks keep up?

The role of finance in enabling the development and implementation of new ideas is vital—an…

-

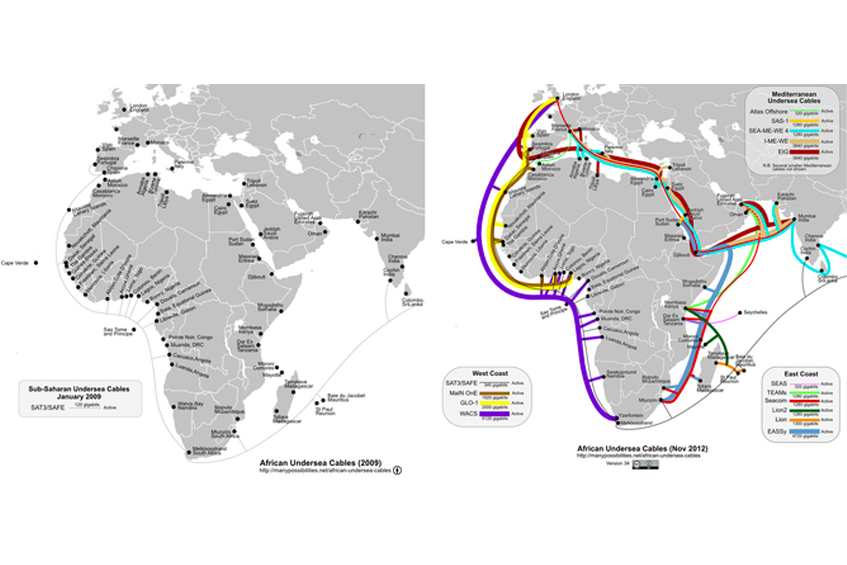

Broadband may be East Africa’s 21st century railway to the world

The excitement over the potentially transformative effects of the internet in low-income countries is nowhere…

-

Investigating virtual production networks in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia

This mass connectivity has been one crucial ingredient for some significant changes in how work…

-

Outside the cities and towns, rural Britain’s internet is firmly stuck in the 20th century

The quality of rural internet access in the UK, or lack of it, has long…

-

Economics for Orcs: how can virtual world economies inform national economies and those who design them?

– in EconomicsUnderstanding these economies is therefore crucial to anyone who is interested in the social dynamics…